Ibn Khaldun (1332 – 1406)

Quick Summary

Ibn Khaldun (1332 – 1406) was a historian and major figure in history. Born in Tunis, Ifriqiya (modern Tunisia), Ibn Khaldun left a lasting impact through Writing the Muqaddima as a methodological introduction to history and social sciences.

Birth

May 27, 1332 Tunis, Ifriqiya (modern Tunisia)

Death

March 17, 1406 Cairo, Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt

Nationality

Ifriqiyan

Occupations

Complete Biography

Origins And Childhood

Abd al-Rahman ibn Muhammad ibn Khaldun was born in Tunis to an Andalusian family of Yemeni origin that had resettled after the Reconquista. Urban life in Ifriqiya granted him access to Maliki jurists, Arabic grammar, mathematics, and philosophy. He memorized the Qur’an, studied Aristotelian logic, and moved within Hafsid scholarly circles. The Black Death struck North Africa during his youth, shaping his sensitivity to social crises.

Historical Context

The 14th-century Maghreb was fragmented among Marinids, Hafsids, Ziyanids, and Nasrids while Saharan and Mediterranean trade routes shifted. Caravans carried gold, enslaved people, and manuscripts; ports like Tunis, Béjaïa, and Fez competed. Plague and warfare weakened states. Ibn Khaldun observed how ‘asabiyya—tribal solidarity—structured authority and how taxation, armies, and religion could bolster or erode dynasties.

Public Ministry

Early in life he served the Marinid chancery in Fez, then the Nasrid court in Granada advising Sultan Muhammad V. As a diplomat between rival kingdoms, he negotiated with Peter I of Castile and acted as envoy to tribal leaders. Back in the central Maghreb he alternated as vizier, secretary, or prisoner amid palace coups. His political career fed his skepticism toward fragile courtly alliances.

Teachings And Message

The Muqaddima crystallized his message: history must be critical, grounded in observation, causality, and economic realities. He proposed a cyclical theory—tribes bound by ‘asabiyya seize power, then decline through luxury before replacement. He stressed the roles of education, climate, agriculture, and trade in societal prosperity. His synthesis merged Islamic jurisprudence, Greek philosophy, and administrative pragmatism.

Activity In Galilee

Seeking seclusion to write, he retired between 1375 and 1377 to Qal‘at Ibn Salama near Tiaret as a guest of the Banu Arif. There he composed the Muqaddima and parts of the ‘Kitab al-‘Ibar.’ This voluntary retreat, far from unstable courts, illustrates his belief that distance sharpens insight into power dynamics.

Journey To Jerusalem

In 1382 he left the Maghreb for Mamluk Egypt. Welcomed by Sultan Barquq, he gained teaching posts at al-Azhar and the office of chief Maliki judge. Rivalries among emirs and critiques of his rigor led to repeated dismissals and reappointments. In 1401 he joined the Cairene delegation to Tamerlane at Damascus; the famed interview shows his diplomatic skill and reflections on conquest and taxation.

Sources And Attestations

His Autobiography—often appended to the ‘Book of Examples’—is the principal source on his life. Maghrebi chroniclers (Ibn al-Khatib, al-Maqqari) and Egyptian writers (al-Suyuti) confirm his public offices. Manuscript copies of the Muqaddima spread from Cairo to Istanbul, testifying to its rapid reception. Mamluk judicial records note his rulings and professional disputes.

Historical Interpretations

Nineteenth-century Orientalists (Silvestre de Sacy, de Slane) translated and commented on his work, revealing his sociological method to Europe. In the twentieth century, scholars like Ernest Gellner, Muhsin Mahdi, and Aziz al-Azmeh emphasized his systemic approach. Debates continue about his debt to Greek philosophy, his empiricism, and the universality of ‘asabiyya. Today he is seen as a precursor to social science and political economy.

Legacy

Dying in Cairo in 1406, Ibn Khaldun left a legacy that transcended Islamic historiography. The Muqaddima influenced modern Arab thinkers, informed analyses of colonialism and modernization, and nourished historical sociology. His name now appears on libraries, universities, and academic chairs across the Arab world and the West.

Achievements and Legacy

Major Achievements

- Writing the Muqaddima as a methodological introduction to history and social sciences

- Analyzing ‘asabiyya as the driving force of dynasties and political cycles

- Serving as judge and diplomat for Maghrebi and Mamluk rulers

- Critically synthesizing Maghrebi and Eastern medieval chronicles

Historical Legacy

Ibn Khaldun remains a key reference for understanding the dynamics of states and societies. His theory of ‘asabiyya illuminates cohesion and fragmentation, and his insistence on source criticism and economic causation inspires historians, sociologists, and economists across the Arab world and beyond.

Detailed Timeline

Major Events

Birth

Born on 27 May in Tunis to a learned Andalusian family

Political beginnings

Joins the Marinid administration in Fez

Mission to Granada

Adviser to Nasrid Sultan Muhammad V, negotiates with Castile

Muqaddima completed

Finishes the introduction to the Book of Examples at Qal‘at Ibn Salama

Settlement in Cairo

Professor and chief Maliki judge under Sultan Barquq

Meeting Tamerlane

Negotiates at Damascus during the Timurid siege

Death

Dies in Cairo after multiple judicial appointments

Geographic Timeline

Famous Quotes

"Civilization is the necessary condition of human life."

"Injustice heralds the ruin of dynasties."

"Victories are achieved only through group strength and solidarity."

External Links

Frequently Asked Questions

When was Ibn Khaldun born and when did he die?

He was born on 27 May 1332 in Tunis and died on 17 March 1406 in Cairo after a lifetime traveling between the Maghreb and Egypt.

What is his most famous work?

The Muqaddima, the prologue to his ‘Book of Examples,’ where he sets out his theory of dynastic cycles, ‘asabiyya, and critical historical method.

What political roles did he hold?

He served as secretary, diplomat, and negotiator for Marinid, Nasrid, and Hafsid rulers, later becoming a Maliki judge and teacher in Cairo.

Why is he seen as a forerunner of sociology?

Because he explained state formation and collapse through social cohesion, economic structures, and collective behavior rather than legend alone.

Which sources document his life?

His own Autobiography and Maghrebi and Egyptian chronicles record his missions, judicial posts, and the writing of the Muqaddima.

Sources and Bibliography

Primary Sources

- Ibn Khaldoun — Kitab al-‘Ibar (Muqaddima)

- Autobiographie d’Ibn Khaldoun

Secondary Sources

- H. R. Idris — Ibn Khaldûn: Essai de biographie intellectuelle

- Muhsin Mahdi — Ibn Khaldun’s Philosophy of History

- Ernest Gellner — Muslim Society

- Aziz al-Azmeh — Ibn Khaldun: An Essay in Reinterpretation

External References

See Also

Related Figures

Confucius

Chinese philosopher, educator, and official of the State of Lu

Genghis Khan

Founder of the Mongol Empire and Eurasian conqueror

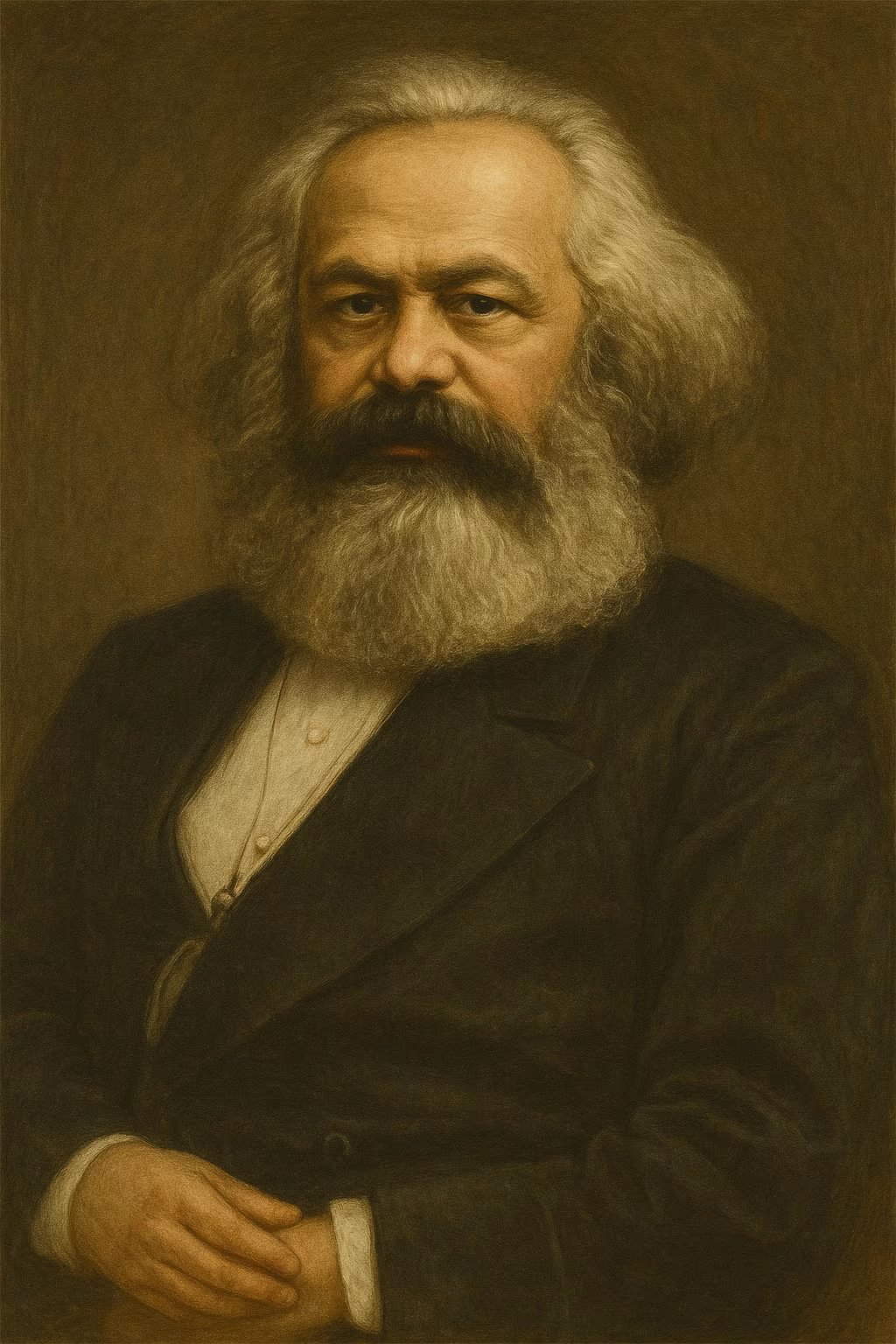

Karl Marx

19th-century philosopher, economist, and social theorist

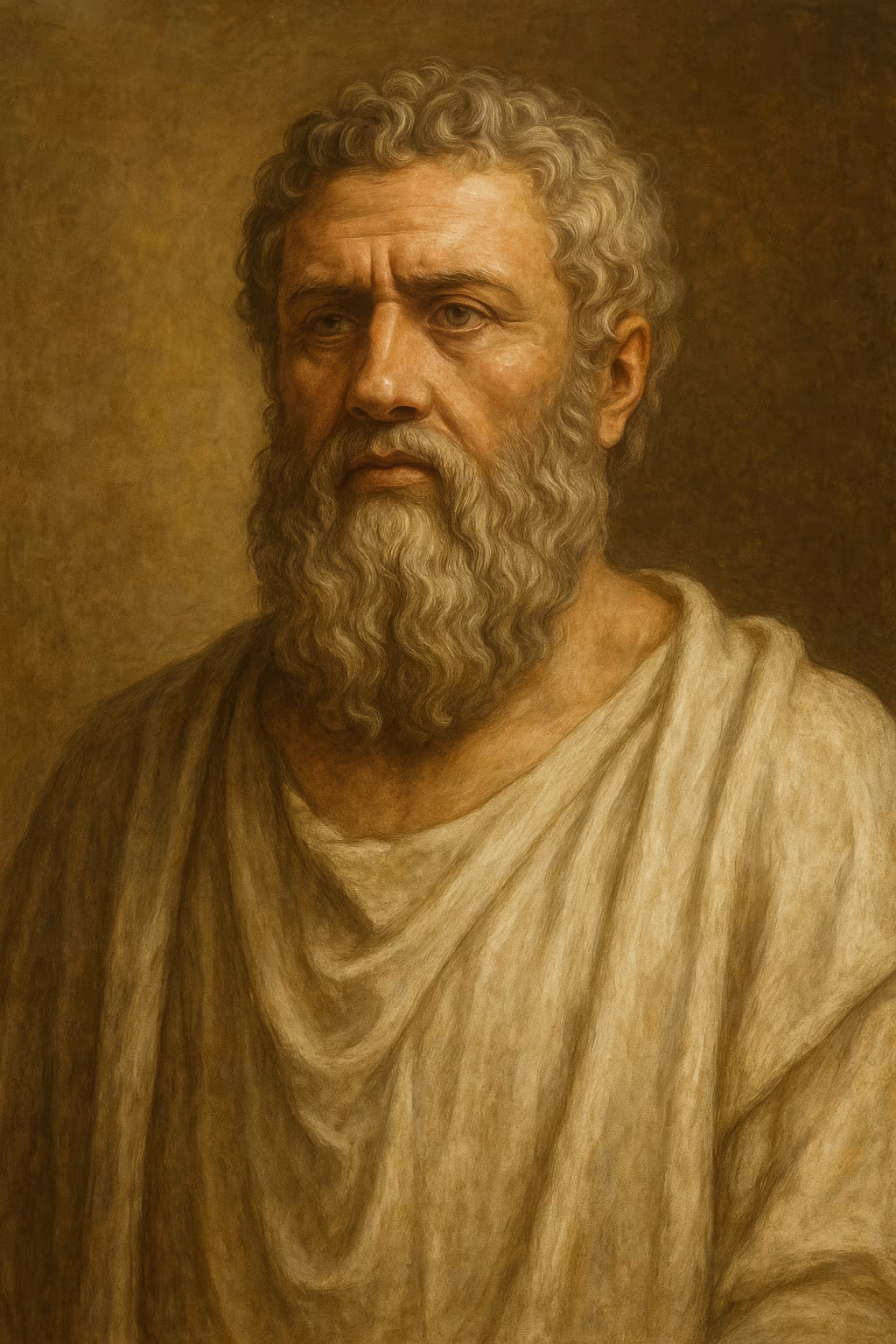

Plato

Greek philosopher, founder of the Academy

Specialized Sites

Batailles de France

Discover battles related to this figure

Dynasties Legacy

Coming soonExplore royal and noble lineages

Timeline France

Coming soonVisualize events on the chronological timeline