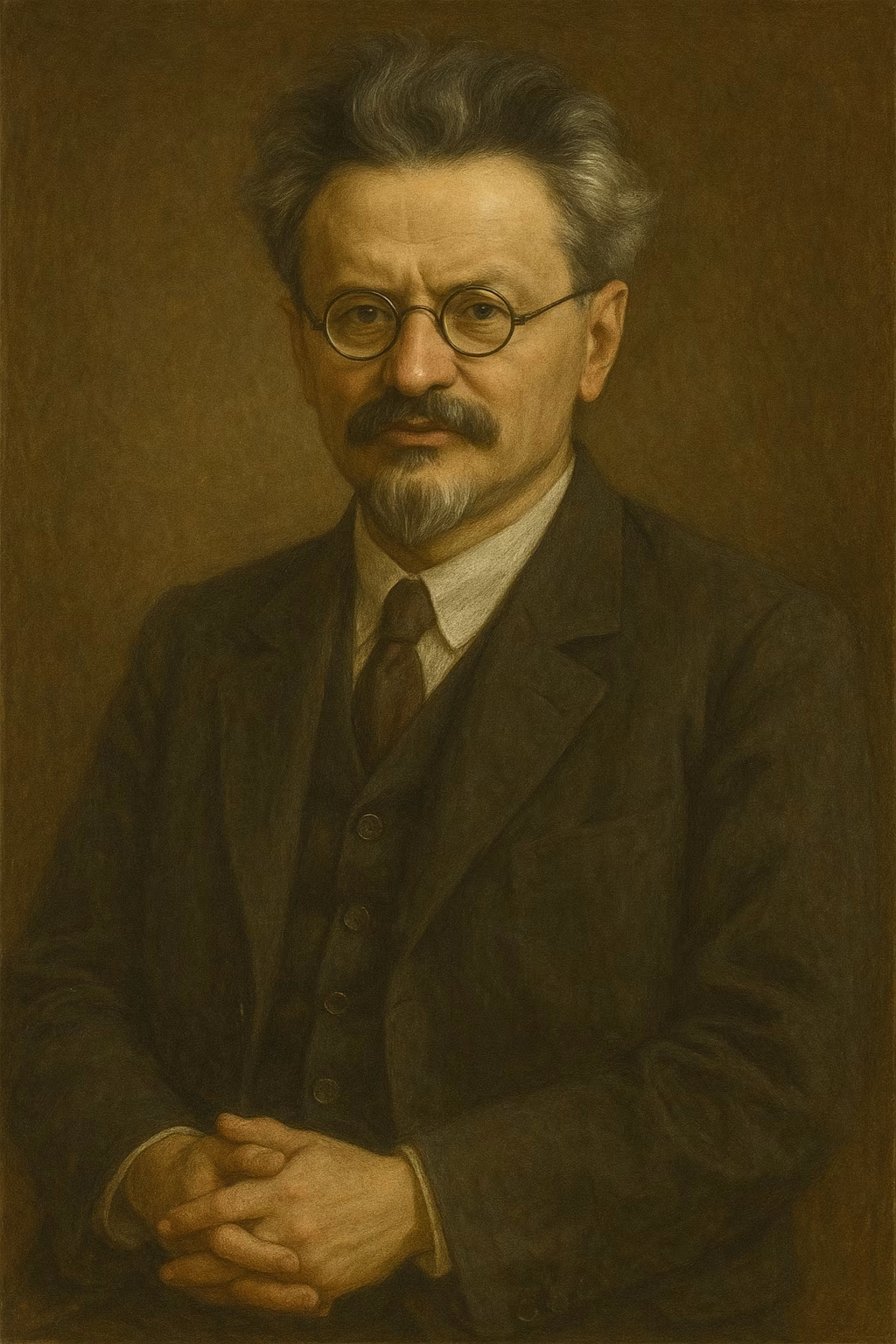

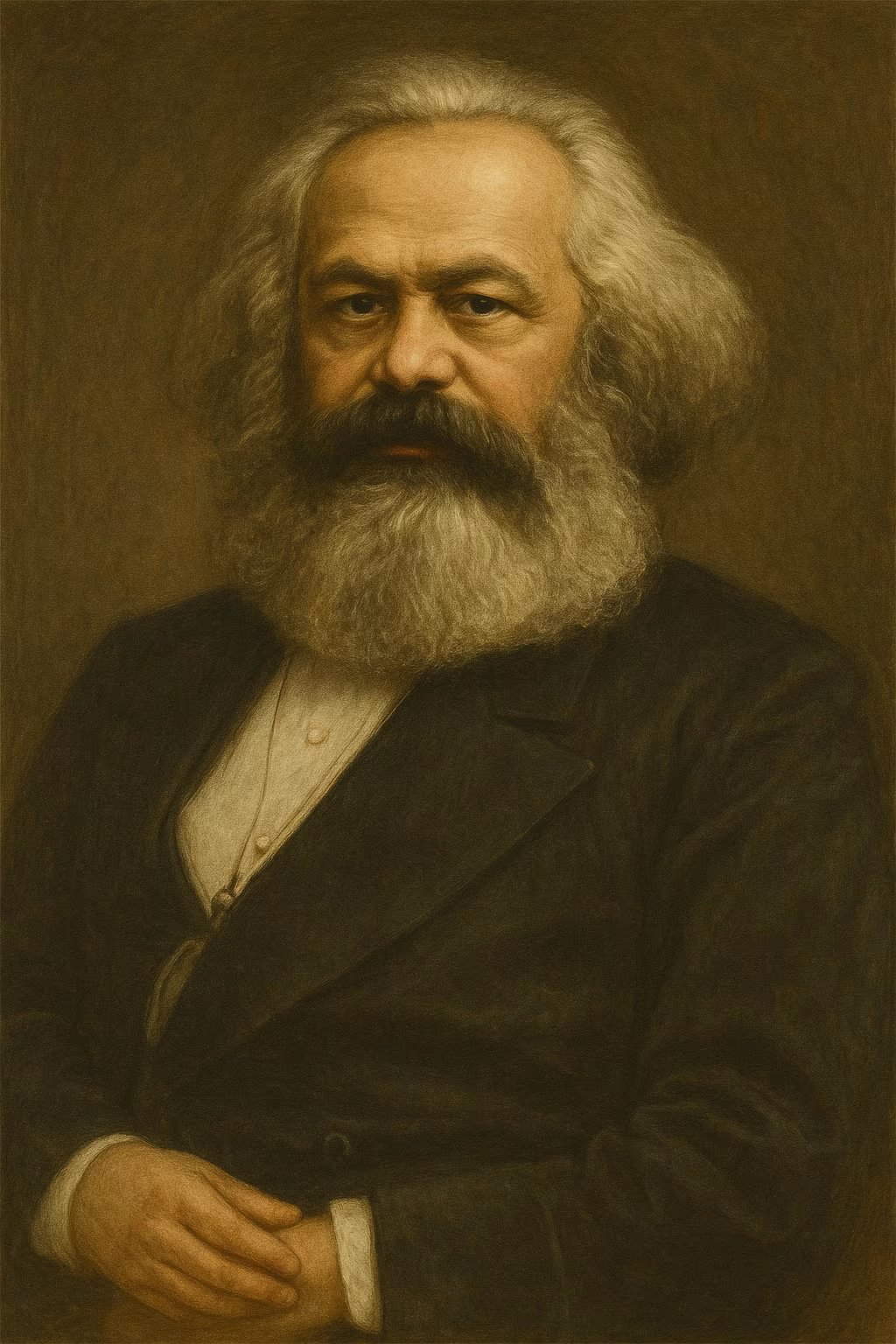

Karl Marx (1818 – 1883)

Quick Summary

Karl Marx (1818 – 1883) was a philosopher and major figure in history. Born in Trier, Province of the Lower Rhine, Kingdom of Prussia, Karl Marx left a lasting impact through Co-authored the Communist Manifesto (1848).

Birth

May 5, 1818 Trier, Province of the Lower Rhine, Kingdom of Prussia

Death

March 14, 1883 London, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

Nationality

Prussian-born stateless resident in Britain

Occupations

Complete Biography

Origins And Childhood

Karl Heinrich Marx was born in 1818 in Trier, a Rhineland city marked by Napoleonic reforms and subsequent Prussian rule. His father Heinrich, a lawyer from a long rabbinical lineage, converted to Protestantism in 1816 to retain his legal practice; his mother Henriette Pressburg came from a prosperous Dutch Jewish family. The household embraced Enlightenment culture, read French literature, and discussed the politics of constitutional reform. Marx attended the Trier Gymnasium, excelling in classical languages and writing essays that betrayed an early interest in history and jurisprudence. At sixteen he drafted a reflection on professional vocation that already framed life as service to humanity. In 1835 he enrolled at the University of Bonn to study law but devoted much time to literary clubs and student duels, prompting his parents to transfer him to Berlin. There, the rigorous intellectual climate exposed him to the Young Hegelian circle, which questioned religion and monarchy. His engagement to Jenny von Westphalen, the enlightened daughter of a Prussian baron, tied him to liberal aristocratic networks and fueled his ambition to reform society through critical philosophy.

Historical Context

The Europe of Marx’s youth was undergoing industrial transformation: textile mills, steam engines, and railways reconfigured labor, while population growth and urban migration produced new social tensions. The Congress of Vienna restored conservative monarchies determined to suppress dissent; in the Rhineland, legal and fiscal reforms introduced under Napoleon clashed with Prussian authoritarianism. Economic crises in 1816–1817 and 1825 highlighted the volatility of global markets. Intellectual debates opposed idealist philosophers, who saw history as the unfolding of Spirit, and materialist critics such as Ludwig Feuerbach, who emphasized human sensuous activity. The emergent working class organized mutual aid societies and staged uprisings: the Lyon silk weavers, the British Chartists, Polish and Italian nationalists. These movements impressed Marx, convincing him that political emancipation required structural change beyond liberal constitutionalism.

Public Activity

After completing a doctoral thesis in 1841 on the philosophies of nature in Democritus and Epicurus, Marx abandoned hopes of a university career: Prussian authorities barred radical Hegelians from academic posts. He turned to journalism and joined the Rheinische Zeitung in Cologne in 1842, critiquing forestry laws, censorship, and bureaucratic abuses. Government suppression of the paper drove him to Paris, where he edited the German-French Annals, debated with Proudhon and Bakunin, and immersed himself in socialist and workers’ associations. His 1844 meeting with Friedrich Engels forged a partnership that blended theoretical insight with financial support. Together they composed the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts and The German Ideology, linking alienation to the structure of wage labor. Expelled from France at Prussia’s request, Marx settled in Brussels, organized German workers’ clubs, and delivered lectures on class struggle. Research trips to London and Manchester introduced him to British political economy, trade unions, and the reality of industrial labor, providing empirical grounding for his critique of capitalism.

Teachings And Message

Marx’s theoretical message centers on historical materialism: social development is driven by changes in the mode of production, and class struggle is the motor of history. He argues that capitalism extracts surplus value from labor, concentrates ownership, and commodifies human relations. Concepts such as alienation, commodity fetishism, and primitive accumulation explain how exploitation is obscured and reproduced. Marx insists on internationalism and the self-emancipation of the proletariat. In the 1848 Communist Manifesto he and Engels portray the bourgeoisie as a revolutionary force that has globalized production, yet created its own gravedigger in the working class. They advocate organization into a political party capable of seizing state power and socializing the means of production. Unlike utopian socialists, Marx emphasizes scientific analysis of economic dynamics, highlighting crises, technological change, and the interconnectedness of world markets, including colonial expansion.

Activity In Europe

Brussels became Marx’s political laboratory. Within the League of the Just, renamed the Communist League, he advocated a program calling for abolition of bourgeois property, progressive taxation, and free public education. The 1848 revolutions propelled him back to Cologne to lead the Neue Rheinische Zeitung, a radical daily championing democratic republics and alliances with the peasantry. Tried for incitement, he was expelled from Prussia and briefly from Paris. Marx settled permanently in London in late 1849, enduring chronic poverty and personal tragedy—several children died in infancy, and he struggled with illness and landlord evictions. He devoted long hours to the British Museum Reading Room, compiling statistics on wages, machinery, and colonial trade. He participated in émigré politics, advised British Chartists, and corresponded incessantly with Engels in Manchester, whose financial assistance kept the family afloat while enabling Marx to continue his research.

Journey To Confrontation

The 1850s and 1860s brought intense polemics and organizational battles. Marx criticized fellow socialists whom he saw as opportunists, including Ferdinand Lassalle and Wilhelm Weitling, and clashed with anarchists gathered around Bakunin. As a European correspondent for the New-York Daily Tribune, he analyzed the 1857 commercial panic, British rule in India, and the American Civil War, praising Abraham Lincoln’s antislavery stance. British police monitored émigré circles but refrained from expulsion, leaving Marx stateless yet relatively secure. In 1864 he helped found the International Working Men’s Association (First International), drafting its inaugural address and statutes. Internal disputes with Proudhonists and Bakuninists climaxed at the 1872 Hague Congress, where Marx defended centralized political organization. The repression that followed the 1871 Paris Commune and Marx’s declining health led to the transfer of the General Council to New York, curtailing his direct leadership. Meanwhile, liver ailments and bronchitis slowed progress on Volumes II and III of Capital, though he continued to study Russian agrarian communes and Irish land reform, reconsidering linear models of social transition.

Sources And Testimonies

Historians draw on a vast documentation: family correspondence, notebooks, economic manuscripts, and journalistic articles. Collections at the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam and the Marx-Engels Gesamtausgabe (MEGA) reveal Marx’s extensive reading in economics, geology, mathematics, and anthropology, as well as unfinished reflections on rent, non-European societies, and mathematics. Accounts by contemporaries such as Wilhelm Liebknecht, Laura Lafargue, and Eleanor Marx portray a devoted family man, sharp-witted conversationalist, and relentless polemicist. Police and judicial reports from Prussia, France, and Belgium detail surveillance of his meetings and speeches, offering external perspectives on his activism. Minutes of the International, London branch records, and trade union reports trace his influence on workers’ strategies. Posthumously published manuscripts—the Grundrisse, Theories of Surplus Value, ethnological notebooks—allow scholars to track the evolution of his thought and challenge portrayals of Marxism as a closed system.

Historical Interpretations

Interpretations of Marx since 1883 span ideological canonization and critical reassessment. Twentieth-century Marxisms ranged from Lenin’s vanguardism to Austro-Marxist gradualism, Western Marxism’s focus on culture (Gramsci, Lukács), and structuralist readings by Louis Althusser. Translations by Joseph Roy, Samuel Moore, and Ben Fowkes shaped reception, influencing how terms like “dictatorship of the proletariat” or “forces of production” were understood. From the 1960s onward, scholars including David McLellan, Terrell Carver, Gareth Stedman Jones, and Hal Draper produced philological and biographical studies emphasizing discontinuities and historical context. The opening of Soviet archives and ongoing MEGA II editions have provided access to mathematical notebooks, Russian correspondence, and preparatory drafts of Capital. Global historians such as Kevin B. Anderson and Jairus Banaji reassessed Marx’s views on colonialism, nationalism, and agrarian communities, highlighting the flexibility and evolving scope of his analysis.

Legacy

Marx’s legacy is multifaceted. His concepts underpin socialist and communist movements, inspiring the Second International, the 1917 Russian Revolution, anti-imperialist struggles, and critiques of neoliberal globalization. His theories of value and crisis animate heterodox economics, while classical sociologists (Weber, Durkheim) engaged his ideas to define their own disciplines. Cultural studies, critical geography, and feminist theory draw on notions of mode of production, ideology, and social reproduction. Beyond regimes claiming his authority, Marx influenced labor campaigns for the eight-hour workday, Bismarckian social insurance, Scandinavian social democracy, and feminist materialism (Alexandra Kollontai, Silvia Federici). Commemorations in 1918, 1968, and 2018 demonstrate his enduring symbolic presence. Contemporary debates on ecological limits, digital capitalism, and global inequality continue to reinterpret his work, confirming its adaptability to changing historical conditions.

Achievements and Legacy

Major Achievements

- Co-authored the Communist Manifesto (1848)

- Published Capital, Volume I (1867)

- Helped found the International Working Men’s Association

- Formulated historical materialism and the theory of surplus value

Historical Legacy

Marx’s ideas shape labor movements, critiques of capitalism, social redistribution policies, and present-day analyses of globalization.

Detailed Timeline

Major Events

Birth

Born in Trier into a liberal-minded family of lawyers

Meeting Engels

Parisian exile and beginning of a decisive intellectual partnership

Communist Manifesto

Publication of the Communist League program amid revolutionary upheavals

First International

Creation of the International Working Men’s Association and drafting of its statutes

Capital, Volume I

Release in Hamburg of the first volume of Marx’s major work

Death

Died in London; buried at Highgate Cemetery

Geographic Timeline

Famous Quotes

"The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point, however, is to change it."

"Workers of all countries, unite!"

"The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles."

External Links

Frequently Asked Questions

When and where was Karl Marx born?

Karl Marx was born on 5 May 1818 in Trier, in the Kingdom of Prussia, to a family of lawyers of Jewish origin who had converted to Protestantism.

What is Marx’s major work?

His major work is Capital; Volume I appeared in 1867 and offered a systematic critique of classical political economy and the capitalist mode of production.

Why did he live in exile?

His attacks on the Prussian monarchy and revolutionary activism led to censorship and expulsions from Germany, France, and Belgium, forcing him to seek refuge in London in 1849.

Which languages did Marx use?

He wrote mainly in German but also published in French and English; his notebooks show ease with Greek, Latin, Russian, and Italian sources.

How did his thought influence history?

Marx’s analyses shaped Marxism, inspiring socialist parties, communist revolutions, critical social sciences, and contemporary debates on inequality.

Sources and Bibliography

Primary Sources

- Karl Marx et Friedrich Engels — Manifeste du parti communiste

- Karl Marx — Le Capital, livre I

- Karl Marx — Grundrisse der Kritik der politischen Ökonomie

- Karl Marx — Correspondance avec Friedrich Engels

- Minutes de l’Association internationale des travailleurs (1864–1872)

Secondary Sources

- David McLellan — Karl Marx: A Biography ISBN: 9780231135937

- Gareth Stedman Jones — Karl Marx: Greatness and Illusion ISBN: 9780674971615

- Mary Gabriel — Love and Capital: Karl and Jenny Marx and the Birth of a Revolution ISBN: 9780316066112

- Kevin B. Anderson — Marx at the Margins: On Nationalism, Ethnicity, and Non-Western Societies ISBN: 9780226019847

- Jonathan Sperber — Karl Marx: A Nineteenth-Century Life ISBN: 9780871407375

External References

See Also

Specialized Sites

Batailles de France

Discover battles related to this figure

Dynasties Legacy

Coming soonExplore royal and noble lineages

Timeline France

Coming soonVisualize events on the chronological timeline