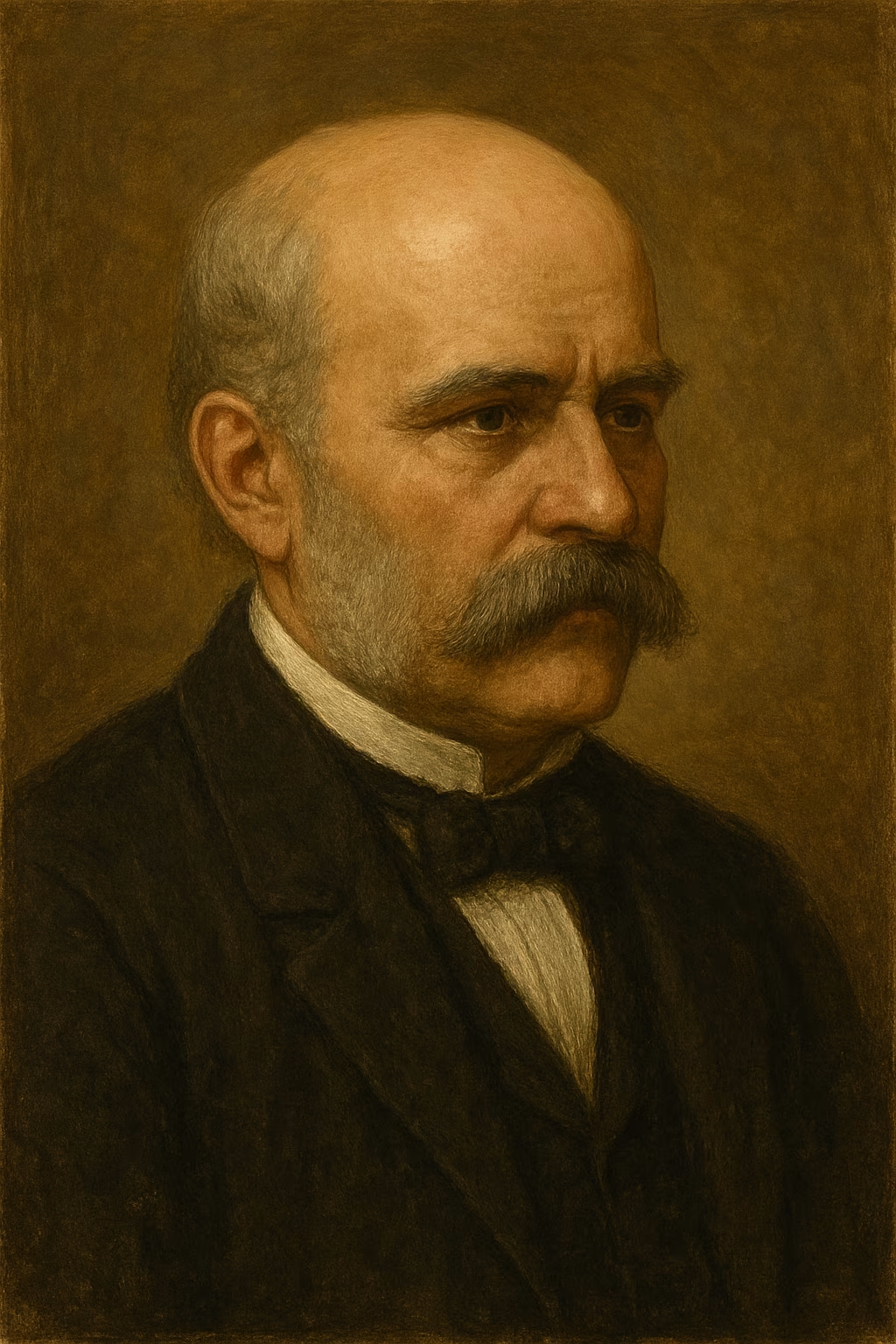

Ignaz Semmelweis (1818 – 1865)

Quick Summary

Ignaz Semmelweis (1818 – 1865) was a obstetrician and major figure in history. Born in Buda, Kingdom of Hungary, Austrian Empire, Ignaz Semmelweis left a lasting impact through Empirical proof that chlorinated-lime handwashing reduced puerperal fever.

Birth

July 1, 1818 Buda, Kingdom of Hungary, Austrian Empire

Death

August 13, 1865 Vienna, Austrian Empire (today Austria)

Nationality

Hungarian

Occupations

Complete Biography

Origins And Childhood

Born on 1 July 1818 in Buda to a prosperous German-speaking merchant family, Semmelweis received a strict education in the multilingual milieu of Hungary's capital. After starting law studies at the University of Pest, he shifted to medicine, drawn by clinical science and social utility. Training in Pest and then Vienna exposed him to anatomy, pathology, and the bustling clinical wards. Fascinated by obstetrics—critical as urban maternity mortality surged—he chose this specialty for its human impact and need for innovation.

Historical Context

Mid-19th-century Europe saw rapid growth of hospital medicine and autopsy-based pathology. Vienna's General Hospital served as a teaching hub where students moved from dissection rooms to maternity wards. Puerperal fever ravaged birthing women, while miasmatic theory dominated and contact transmission was doubted. Political upheavals of 1848 and national tensions within the Habsburg Empire colored academic debates. Public scrutiny of maternal deaths pushed clinicians to seek pragmatic remedies. Comparing outcomes between hospital wards and home births highlighted the urgency of reform and provided space for empirical innovators like Semmelweis.

Public Ministry

Appointed assistant at Vienna's First Obstetrical Clinic in 1846, Semmelweis faced mortality rates exceeding 15%. He compared the physician-staffed ward, where students performed autopsies, with the midwife-run ward that reported far fewer deaths. Searching for a causal factor, he turned to data. Kolletschka's fatal wound during an autopsy in 1847 suggested that cadaveric particles on physicians' hands might kill mothers. Semmelweis mandated handwashing with chlorinated lime before examinations, and mortality plummeted to below 2%—an astonishing turnaround.

Teachings And Message

Semmelweis preached rigorous hand hygiene as an ethical duty. He gathered statistics, staged demonstrations, and demanded strict compliance from students. His message emphasized empirical observation, prevention, and accountability. By prioritizing bedside data over prevailing theory, he foreshadowed modern epidemiology. Daily discipline—washing hands, cleaning instruments, improving ventilation—formed a blueprint for later antiseptic practice and patient-safety culture.

Activity In Galilee

After clashes with Vienna's hierarchy and the upheavals of 1848, Semmelweis returned to Pest in 1850. At Saint Roch Hospital he enforced chlorinated-lime handwashing and again slashed puerperal mortality. Teaching midwives and physicians, he adapted protocols to local constraints and promoted teamwork. Hungary's limited resources did not prevent success: his results proved that consistent hygiene could work even in modest facilities. He also engaged with Hungarian medical societies to disseminate his data.

Journey To Jerusalem

Resistance intensified. In Vienna, leaders resented his implied criticism; in Pest, some peers doubted chlorinated lime or felt personally attacked. His 1861–1862 open letters condemned inaction and framed puerperal fever deaths as preventable. The polemics eroded his standing in academic circles. Publishing late and in dense form, and lacking a germ theory, he struggled to win broad acceptance despite compelling numbers.

Sources And Attestations

Semmelweis's 1861 treatise compiles mortality tables, case narratives, and protocols. Hospital records from Vienna and Pest corroborate dramatic declines during handwashing enforcement. Medical journals of the era and correspondence with figures such as Hebra and Michaelis document the controversy. Reports from Austrian and Hungarian medical societies reflect the heated debates his claims provoked.

Historical Interpretations

Historians depict Semmelweis as a data-driven pioneer hampered by contemporary theory and institutional inertia. His rigorous statistics and insistence on prevention align with evidence-based medicine. Yet his combative tone and isolation contributed to slow adoption. In the wake of Pasteur and Lister, his work was reinterpreted as a crucial step toward antisepsis. Recent analyses highlight his epidemiological insight, methodological strictness, and ethical commitment to preventing avoidable suffering.

Legacy

Modern hospital hygiene protocols—systematic handwashing, instrument disinfection, safety culture—bear Semmelweis's imprint. Hospitals, awards, and the Semmelweis University in Budapest honor his name. His story illustrates both resistance to innovation and the power of clinical data. Belated recognition helped entrench antiseptic measures and drastically reduce nosocomial infections worldwide.

Achievements and Legacy

Major Achievements

- Empirical proof that chlorinated-lime handwashing reduced puerperal fever

- Implementation of hand hygiene at Vienna General Hospital in 1847

- Extension of antiseptic protocols to Saint Roch Hospital in Pest

- Publication of 'The Etiology, Concept and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever' in 1861

- Foundational influence on hospital antisepsis and infection prevention

Historical Legacy

Ignaz Semmelweis symbolizes the birth of modern medical hygiene. His insistence on handwashing launched a safety culture that saves millions of lives. Despite early opposition, his name is now synonymous with antisepsis, clinician accountability, and evidence-based practice.

Detailed Timeline

Major Events

Birth

Born in Buda, Kingdom of Hungary

Assistant in Vienna

Assumes post at the First Obstetrical Clinic, Vienna General Hospital

Handwashing discovery

Mandates chlorinated-lime handwashing; puerperal fever rates collapse

Return to Pest

Implements protocols at Saint Roch Hospital

Major publication

Releases treatise on childbed fever etiology and prevention

Death

Dies in Vienna from sepsis

Geographic Timeline

Famous Quotes

"The doctor is responsible for what clings to his hands."

"Statistics have a voice that cannot be ignored."

"Ignorance is no excuse when lives are at stake."

External Links

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is Ignaz Semmelweis notable?

He proved in 1847 that handwashing with chlorinated lime slashed puerperal fever rates, foreshadowing antiseptic practice.

Where did he work?

Mainly at Vienna General Hospital and later at Saint Roch Hospital in Pest, where he continued enforcing hygiene protocols.

Why were his findings resisted?

They contradicted miasma theory and implied that physicians themselves transmitted deadly infections, a notion many rejected.

When were his ideas accepted?

Broad acceptance followed the antiseptic successes of Lister and the germ theory advances of Pasteur and Koch after 1867.

How did he die?

He died in 1865 in a Viennese asylum from sepsis, a tragic end for the champion of hand hygiene.

Sources and Bibliography

Primary Sources

- Ignaz Semmelweis — Die Ätiologie, der Begriff und die Prophylaxis des Kindbettfiebers (1861)

- Ferdinand von Hebra — Articles dans Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift (1847-1848)

- Oliver Wendell Holmes — The Contagiousness of Puerperal Fever (1843)

Secondary Sources

- Sherwin B. Nuland — The Doctor's Plague: Germs, Childbed Fever, and the Strange Story of Ignac Semmelweis ISBN: 9780393326253

- K. Codell Carter — Childbed Fever: A Scientific Biography of Ignaz Semmelweis ISBN: 9781412806662

- Louis-Ferdinand Céline — La Vie et l'Œuvre de Philippe Ignace Semmelweis (thèse, 1924)

- G. B. Gordon — Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis et la fièvre puerpérale

External References

See Also

Related Figures

Specialized Sites

Batailles de France

Discover battles related to this figure

Dynasties Legacy

Coming soonExplore royal and noble lineages

Timeline France

Coming soonVisualize events on the chronological timeline