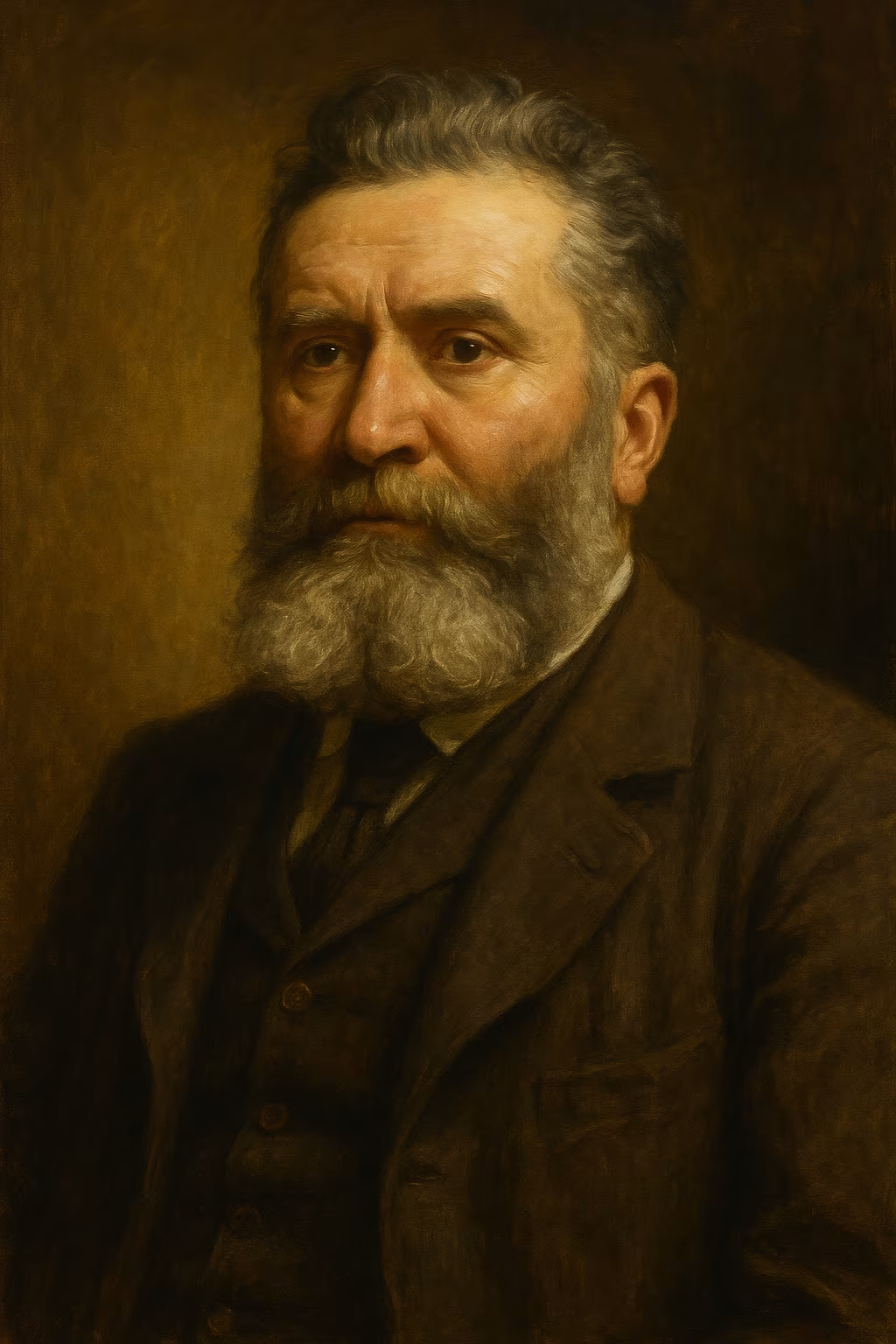

Jean Jaurès (1859 – 1914)

Quick Summary

Jean Jaurès (1859 – 1914) was a politician and major figure in history. Born in Castres, Tarn, Second French Empire, Jean Jaurès left a lasting impact through Defense of Captain Dreyfus and assertion of republican rule of law.

Birth

September 3, 1859 Castres, Tarn, Second French Empire

Death

July 31, 1914 Paris, French Third Republic

Nationality

French

Occupations

Complete Biography

Origins And Childhood

Jean Jaurès grew up in Castres within a modest provincial bourgeois family, navigating between Tarn’s rural traditions and the social ascent promised by republican schooling. A brilliant student at the lycées of Castres and Albi, he excelled in the national concours and entered the École normale supérieure in 1878. In Paris he immersed himself in philosophy, encountered advanced republican circles, and forged a solid classical culture paired with a burgeoning social conscience. After passing the agrégation in philosophy in 1881, he taught in Albi and Toulouse. Classroom experience among provincial youth deepened his empathy for working families and convinced him that emancipation required public education. His Latin thesis on Fichte explored liberty, nationhood, and solidarity, foreshadowing the synthesis that would characterize his later political ideas.

Historical Context

Jaurès acted amid the fragile French Third Republic, born from the defeat of 1870 and the trauma of the Paris Commune. Monarchists contested the republican settlement while industrial capitalism sharpened social inequalities. Workers organized unions and cooperatives, and the rural Southwest oscillated between radical republicanism and social Catholicism. Internationally, Europe entered the age of imperial rivalries and Franco-German tension. Nationalism, arms races, and rising socialist parties framed the era. For Jaurès the crucial question was how to connect parliamentary democracy, social justice, and peace among nations.

Public Ministry

Jaurès entered politics at twenty-six, elected as a moderate republican deputy for Tarn in 1885. He defended secular education, administrative decentralization, and dialogue with Carmaux miners. Defeated in 1889, he returned to Toulouse municipal politics, strengthened ties with the labor movement, and moved closer to socialist activists he had once criticized. The Carmaux glassworkers’ strike of 1892 marked a watershed. Called upon by the workers, he became their spokesman and won the 1893 by-election as a socialist independent. He soon delivered landmark speeches on the eight-hour day, workers’ pensions, and progressive taxation, electrifying the Chamber and gaining national prominence.

Teachings And Message

Jaurès fused republican heritage with Marxist analysis. He portrayed the French Revolution as the cradle of political rights but insisted that those gains must extend to social equality. The Republic, in his view, had to be democratic, secular, social, and open to working people. He promoted cooperation, democratically planned economy, and gradual electoral advances toward socialism. Rejecting violent rupture, he argued for a moral and civic revolution including peasants and workers. His defense of laïcité formed part of an inclusive nation, where spiritual diversity coexisted under a state guaranteeing freedom.

Activity In Galilee

Based in Toulouse and the mining basin of Carmaux, Jaurès organized rallies, lectures, and tours throughout the Southwest. He engaged with worker cooperatives, supported Midi winegrowers battling phylloxera, and encouraged secular teachers to spread accessible republican culture. His local roots enabled experiments in municipal socialism: support for school canteens, public libraries, and mutual aid. Socialist circles around him became civic education laboratories where Marx and Michelet were read side by side and where women slowly gained visibility despite lacking political rights.

Journey To Jerusalem

The Dreyfus Affair thrust Jaurès into national turmoil. From 1894 he demanded a retrial for the Jewish officer accused of treason, exposed fabrications in the file, denounced antisemitism, and urged the army to serve justice. Articles in La Dépêche, La Petite République, and L’Aurore brought threats and smear campaigns. At the same time he sought to bridge socialist divisions between ministerial participation and revolutionary purity. His critical support for the Waldeck-Rousseau cabinet and dialogues with revolutionary syndicalists sparked fierce controversies. The 1904 Amsterdam Congress of the Second International pitted him against Rosa Luxemburg and German delegates over the general strike, highlighting tensions between national strategies and international solidarity.

Sources And Attestations

Transcripts of Jaurès’s parliamentary speeches, collected in the volumes La République et le Socialisme, remain key sources for his rhetoric. Editorials from L’Humanité, founded on April 18, 1904, chart his daily stance on social and international issues. Private correspondence preserved in French national archives reveals activist networks around him. Testimonies by contemporaries such as Léon Blum, Marcel Sembat, and Anatole France illuminate his persuasive force and the fervor he inspired among young socialists.

Historical Interpretations

Historians have offered varied readings. Interwar socialists cast him as a martyr for peace, while communists emphasized his late rapprochement with Marxism. Scholars like Jean-Pierre Rioux, Madeleine Rebérioux, and Vincent Duclert underscore the coherence of a humanist socialism blending republican patriotism and worker internationalism. Current debates revisit his stance on secularism, his concept of a republican army, and his economic foresight. Some stress his pragmatic reformism; others his prophetic warnings against nationalism. His ideas still inform studies of social democracy, ethics of responsibility, and peace strategies.

Legacy

Jaurès’s assassination on July 31, 1914, provoked national and international grief. His funeral united workers, intellectuals, and lawmakers mourning the silencing of a European peace advocate. After the war, his legacy nourished the SFIO, the CGT, and pacifist movements. Léon Blum drew upon his combative parliamentarianism and transformative ambition. In public memory Jaurès symbolizes political courage tied to social justice. His speeches are taught in schools, statues rise across France, and his name graces avenues, metro stations, and schools. His maxim “go to the ideal and understand the real” still guides progressive engagement and shapes contemporary reflections on leadership responsibility during crises.

Achievements and Legacy

Major Achievements

- Defense of Captain Dreyfus and assertion of republican rule of law

- Creation of L’Humanité as the socialist daily

- Unification of French socialists within the SFIO in 1905

- Promotion of internationalist pacifism and advanced social policy

Historical Legacy

A founding figure of French socialism, Jean Jaurès embodied eloquence, social justice, and pacifism. His vision of a social republic continues to inspire progressive movements and remains a moral reference in contemporary political debate.

Detailed Timeline

Major Events

Birth

Born in Castres, Tarn

Election to parliament

Entered the Chamber of Deputies as a moderate republican

Carmaux strike

Supported the glassworkers and embraced militant socialism

Founded L’Humanité

Created the socialist daily newspaper in Paris

Globe Congress

Unified French socialists in the SFIO

Assassination

Killed at the Café du Croissant in Paris

Geographic Timeline

Famous Quotes

"Courage is to seek the truth and speak it."

"Capitalism bears war within it as clouds bear storms."

"Reach for the ideal while understanding the real."

External Links

Frequently Asked Questions

When was Jean Jaurès born and when did he die?

Jean Jaurès was born on 3 September 1859 in Castres, Tarn, and was assassinated on 31 July 1914 at the Café du Croissant in Paris on the eve of the First World War.

What role did he play in the Dreyfus Affair?

From 1894 onward he campaigned for a retrial, used his parliamentary seat and journalism to expose judicial errors, and framed the case as a defense of republican legality against nationalist passions.

Why did he found L’Humanité?

He launched the newspaper in 1904 to give the labor movement an independent press, amplify social struggles, and support the reunification of socialist forces.

What were his views on war?

A committed pacifist, Jaurès advocated international arbitration, easing tensions among European powers, and worker solidarity across borders to prevent war—stances that earned admiration and fierce opposition.

What were his major writings?

Beyond his speeches, he authored the multi-volume Socialist History of the French Revolution, numerous L’Humanité articles, and theoretical essays blending Marxism and republicanism.

Sources and Bibliography

Primary Sources

- Jean Jaurès — Histoire socialiste de la Révolution française

- Jean Jaurès — Discours parlementaires (1885-1914)

- Jean Jaurès — Articles de L’Humanité (1904-1914)

Secondary Sources

- Madeleine Rebérioux — La République radicale ? 1898-1914 ISBN: 9782020063847

- Jean-Pierre Rioux — Jean Jaurès ISBN: 9782070740287

- Vincent Duclert — Jaurès ISBN: 9782262042782

- Gilles Candar et Vincent Duclert — Jean Jaurès, l’intégrale des discours ISBN: 9782021005228

- Serge Berstein — Histoire du Parti socialiste ISBN: 9782130632153

External References

See Also

Related Figures

Charles de Gaulle

Leader of Free France and founding president of the Fifth Republic

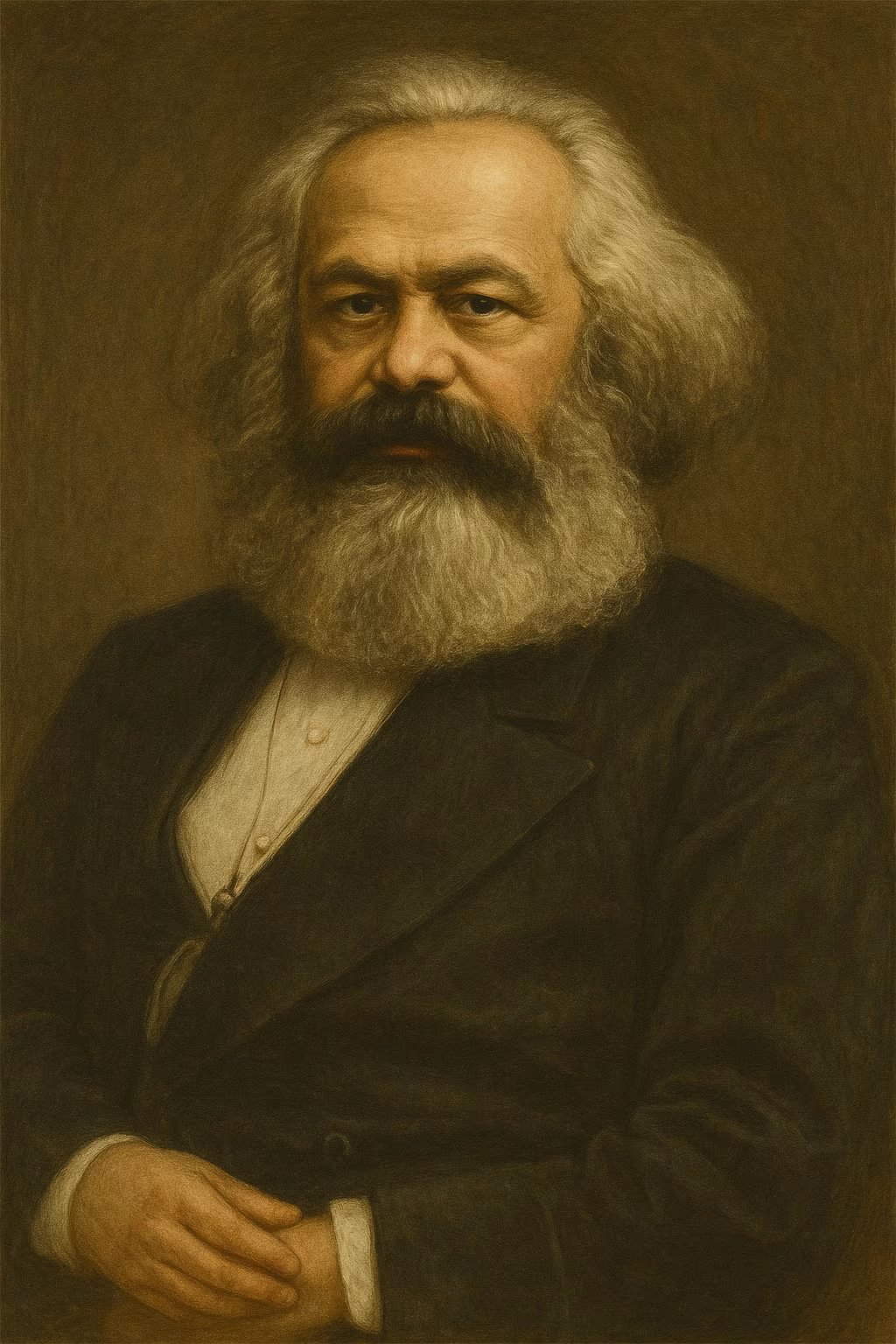

Karl Marx

19th-century philosopher, economist, and social theorist

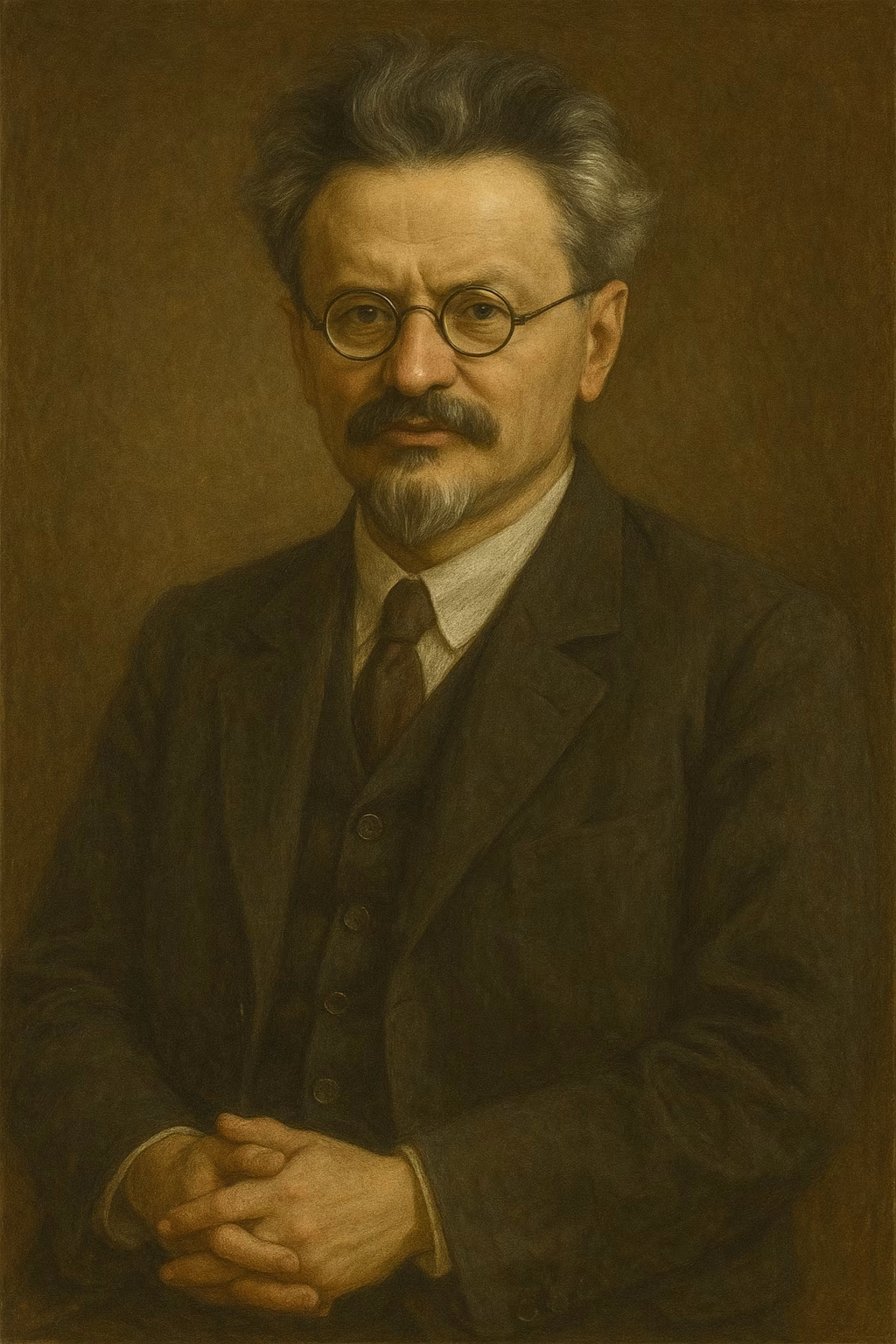

Leon Trotsky

Russian revolutionary, military strategist, and Marxist theorist

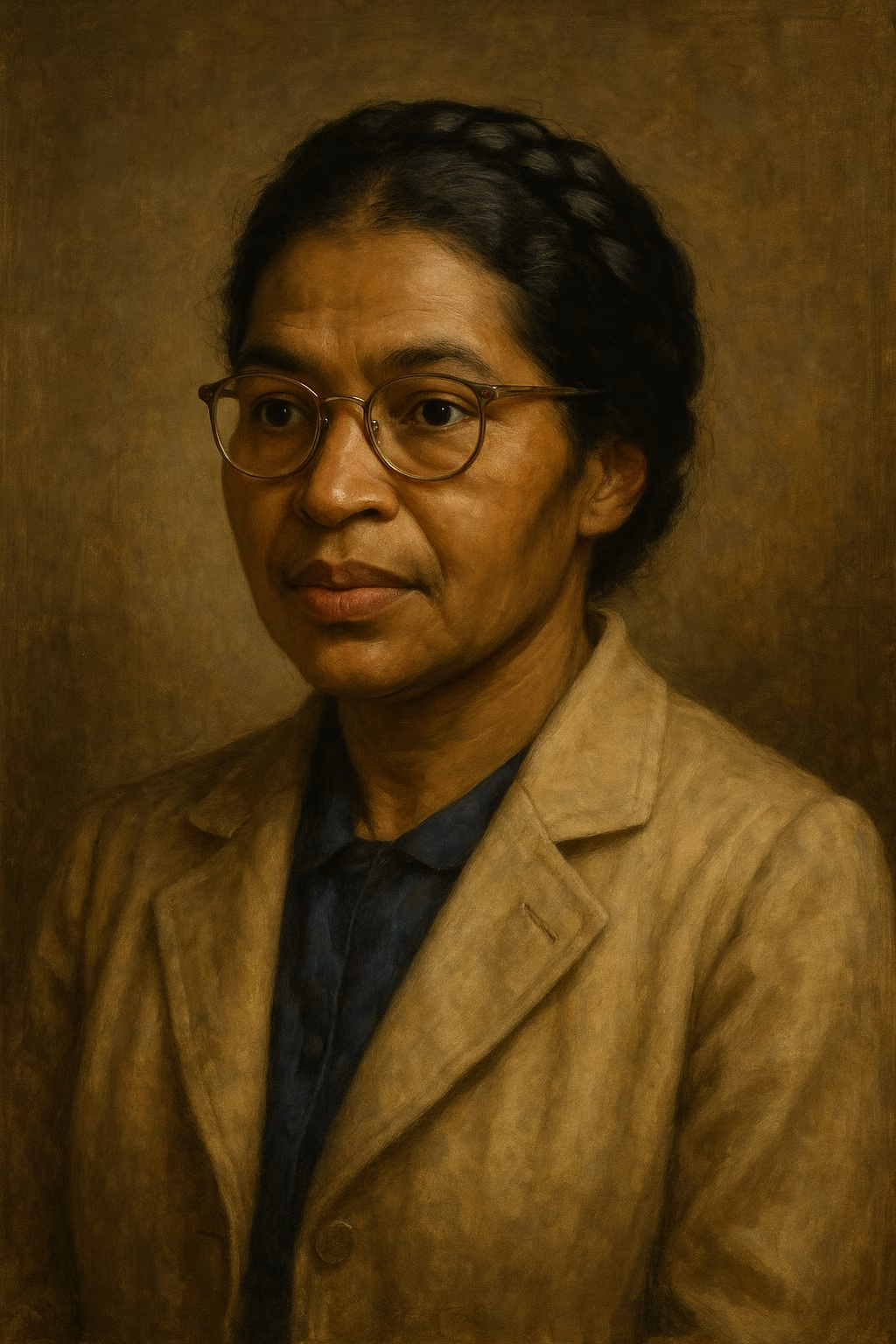

Rosa Parks

African-American civil rights activist

Specialized Sites

Batailles de France

Discover battles related to this figure

Dynasties Legacy

Coming soonExplore royal and noble lineages

Timeline France

Coming soonVisualize events on the chronological timeline