Charles de Gaulle (1890 – 1970)

Quick Summary

Charles de Gaulle (1890 – 1970) was a career army officer and major figure in history. Born in Lille, Nord, France, Charles de Gaulle left a lasting impact through Issued the Appeal of 18 June 1940 and organized Free France.

Birth

November 22, 1890 Lille, Nord, France

Death

November 9, 1970 Colombey-les-Deux-Églises, Haute-Marne, France

Nationality

French

Occupations

Complete Biography

Origins And Childhood

Born into a Catholic and monarchist family in Lille, Charles de Gaulle grew up in a cultivated milieu steeped in national history. His father Henri taught literature and history, while his mother Jeanne instilled fervent patriotism. Educated at Jesuit colleges in Paris and Lille, he developed a fascination for strategy and the Napoleonic epic. Entering the Saint-Cyr military academy in 1909, he graduated as an infantry lieutenant in 1912 and joined the 33rd Regiment commanded by Colonel Pétain, forging a rigorous sense of discipline and a belief in modern, offensive warfare. Early postings in Arras and Saint-Omer confirmed his temperament. He took part in staff exercises, wrote tactical notes, and devoured philosophical writers such as Bergson and Péguy. He nurtured a mystical view of France’s historical mission, tempered by respect for prewar military hierarchies still haunted by 1870.

Historical Context

De Gaulle’s birth coincided with France’s turbulent Third Republic, marked by the Dreyfus Affair, church-state separation, and imperial expansion. The army debated doctrine—offensive élan versus methodical defense—while Europe simmered with alliances, arms races, and nationalist rivalries. World War I erupted in 1914, confirming fears of total war. France mobilized millions; battles ravaged the north and east. As a young lieutenant, de Gaulle discovered the brutal limits of traditional command. Wounded five times and captured at Verdun in March 1916, he spent twenty-seven months in German captivity, repeatedly attempting escape and studying Clausewitz and Foch. The experience revealed the need for mechanized innovation. The interwar years left France victorious yet anxious amid European instability, rising totalitarianism, and economic crisis. De Gaulle observed political rigidity, colonial dependence, and a defense strategy anchored to the Maginot Line, all feeding his pessimism about national decline.

Public Ministry

Between the wars, de Gaulle built a staff career, teaching at the War College and publishing bold analyses. In The Army of the Future (1934) he advocated autonomous armored divisions and shock tactics. Though largely ignored by a nation wedded to static defense, his ideas attracted politicians such as Paul Reynaud. The collapse of May-June 1940 thrust him forward: as colonel commanding the 4th Armored Division he mounted delaying counterattacks, was promoted brigadier general, and appointed undersecretary for war on 6 June. Rejecting the armistice signed by Marshal Pétain, he flew to London and delivered the Appeal of 18 June via the BBC, launching the Free French movement. From Carlton Gardens he organized Free French forces, rallied African colonies, established a national committee, and joined campaigns from North Africa to Normandy. Despite Allied mistrust, his insistence on French sovereignty ensured recognition. After Paris’s liberation he headed the Provisional Government, restored republican institutions, nationalized strategic sectors, and created the social security system.

Teachings And Message

Gaullist doctrine revolved around recurring principles: France’s grandeur, national independence, and unity above party conflict. De Gaulle distrusted fractious parliamentarianism and championed a strong executive able to arbitrate and decide. His speeches—from London to Bayeux, Brazzaville to Algiers—read as lessons in history and civic morality, celebrating national destiny, state continuity, and the necessity of courage. He also valued popular participation through referendums, outreach to youth, and dialogue with unions. His social vision, influenced by Catholic social teaching and solidarism, promoted worker participation and social justice without collectivism. Internationally he advanced a “certain idea of France”: allied yet free, European yet sovereign, oriented toward the Francophonie and the global South.

Activity In Galilee

During the 1940s and 1950s, de Gaulle’s travels across Free French territories and colonial holdings—Brazzaville, Algiers, Casablanca, London, Moscow, Washington—sought to legitimize his movement, secure resources, and affirm state continuity. After 1944 his triumphal tours of liberated France, from Bayeux to Strasbourg, galvanized public morale and reasserted governmental authority. As president (1959–1969) he toured metropolitan France, overseas departments, and former colonies to promote the new republic and cooperation. The 1960 African journey accompanied decolonization; the 1967 visit to Canada culminated in the dramatic “Vive le Québec libre!” Each trip formed part of a broader strategy of outreach and popular diplomacy.

Journey To Jerusalem

De Gaulle’s “journey to Jerusalem” mirrors his return to power amid the Algerian crisis. In May 1958 an insurrection in Algiers threatened the Fourth Republic. Summoned by the army and segments of the political class, de Gaulle demanded full constituent powers and a mandate to craft a new constitution. On 1 June the Assembly named him prime minister; on 4 June in Algiers he declared “Je vous ai compris,” emblematic of his ambiguous balancing act. Drafted under Michel Debré, the 1958 constitution strengthened the presidency, introduced referendums, and promised governmental stability. Opposition parties—communists, supporters of French Algeria—warned of authoritarian drift. De Gaulle navigated between the army, settlers, and Algerian nationalists, opening secret talks with the FLN. The OAS terror campaign, the week of barricades, and the April 1961 generals’ putsch highlighted extremist resistance. The Evian Accords of March 1962 ended the Algerian War and triggered the exodus of European settlers, sealing his final break with the colonial army.

Sources And Attestations

De Gaulle’s career is extensively documented. His own writings—War Memoirs, Speeches and Messages, Memoirs of Hope—present a teleological narrative of his actions. Archives from the Service Historique de la Défense, Foreign Ministry, and the Charles de Gaulle Foundation provide complementary evidence. Testimonies from close collaborators—Georges Pompidou, André Malraux, Jacques Foccart, René Pleven—offer insight into decision-making. Allied sources illuminate tense relations with Churchill and Roosevelt. Historians also draw on intelligence reports, parliamentary debates, radio broadcasts, and newsreels, forming a rich corpus for understanding Gaullism’s construction.

Historical Interpretations

Since the 1970s, historians have oscillated between hagiography and critique. Jean Lacouture, Éric Roussel, Julian Jackson, Maurice Vaïsse, and Frédéric Turpin emphasize his ability to embody the nation in crisis. Some stress his pragmatic economics; others highlight social conservatism or colonial ambiguities. Debate centers on Gaullism’s nature: a unifying movement above parties or a national-conservative ideology? Political scientists see a model of strong presidentialism; sociologists analyze its myth-making power. Critics underline his distrust of counter-powers, combative relations with the press, and skepticism toward supranational Europe. Nonetheless most agree on the coherence of his project: restoring France’s freedom of decision in a bipolar world.

Legacy

De Gaulle’s legacy is multifaceted. Institutionally he left a stable Fifth Republic that has endured numerous alternations of power. Diplomatically he secured nuclear deterrence, a permanent UN Security Council seat, and an independent policy toward the Arab world and Africa. Economically he launched the 1958 stabilization plan, major industrial programs (Caravelle, Concorde, Diamant), and created the DATAR to balance regional development. Socially he promoted worker participation, vocational training, and the 1967 social security reform. His symbolic heritage remains potent: statues, museums, commemorations, and political rhetoric invoking the “spirit of 18 June.” The Charles de Gaulle Foundation, Institute, and Colombey memorial sustain collective memory. In popular culture he endures as a tutelary figure of French resilience, central to debates on sovereignty, Europe, and globalization.

Achievements and Legacy

Major Achievements

- Issued the Appeal of 18 June 1940 and organized Free France

- Unified internal and external Resistance under the CFLN and later the Provisional Government

- Restored state authority and laid the foundations of the welfare state after liberation

- Founded the Fifth Republic and served as its first president

- Negotiated the Evian Accords ending the Algerian War

- Asserted France’s diplomatic and nuclear independence

Historical Legacy

Charles de Gaulle left France with a durable constitutional framework, a diplomacy grounded in sovereignty, and a national memory of resistance. His thought continues to shape debates on state authority, Europe’s future, and how nations can retain strategic autonomy amid globalization.

Detailed Timeline

Major Events

Birth

Born in Lille into a patriotic Catholic family

Verdun

Wounded and captured while commanding his company at Verdun

The Army of the Future

Published his strategic essay advocating mechanized professional forces

Appeal of 18 June

From London he called on the French to continue fighting Nazi Germany

Liberation of Paris

Took charge of the Provisional Government after the Paris uprising

Return to power

Became prime minister and launched drafting of the Fifth Republic’s constitution

Evian Accords

Ended the Algerian War and recognized independence

Resignation

Left the presidency after losing the regionalization referendum

Death

Died suddenly at Colombey-les-Deux-Églises

Geographic Timeline

Famous Quotes

"France cannot be France without greatness."

"All my life I have had a certain idea of France."

"Vive le Québec libre!"

"Logistics will follow."

External Links

Frequently Asked Questions

When was Charles de Gaulle born and when did he die?

He was born on 22 November 1890 in Lille and died on 9 November 1970 in Colombey-les-Deux-Églises from an aneurysm.

What role did he play during World War II?

As undersecretary of war in June 1940 he rejected the armistice, issued the Appeal of 18 June from London, and led Free France, unifying Resistance movements and colonial forces.

How did he found the Fifth Republic?

Recalled amid the May 1958 crisis, de Gaulle secured constituent powers, oversaw drafting of a new constitution that strengthened the executive, and became the Fifth Republic’s first president in January 1959.

What was his foreign policy vision?

He advocated national independence: leaving NATO’s integrated command, recognizing the People’s Republic of China, vetoing Britain’s entry into the EEC, and promoting a Europe of sovereign states.

What writings did he leave?

His War Memoirs (1954–1959) and Memoirs of Hope (1970–1971) blend political justification, historical narrative, and a vision of France’s destiny.

Sources and Bibliography

Primary Sources

- Charles de Gaulle – Mémoires de guerre (3 vol.)

- Discours et messages, 1940-1969

- Fondation Charles-de-Gaulle – Chronologie du Général

Secondary Sources

- Jean Lacouture – De Gaulle (3 tomes) ISBN: 9782070732480

- Éric Roussel – Charles de Gaulle ISBN: 9782213627319

- Julian Jackson – De Gaulle ISBN: 9780674987210

- Maurice Vaïsse – La grandeur. Politique étrangère du général de Gaulle ISBN: 9782746737236

- Frédéric Turpin – De Gaulle, les États-Unis et l’Algérie ISBN: 9782130621845

See Also

Related Figures

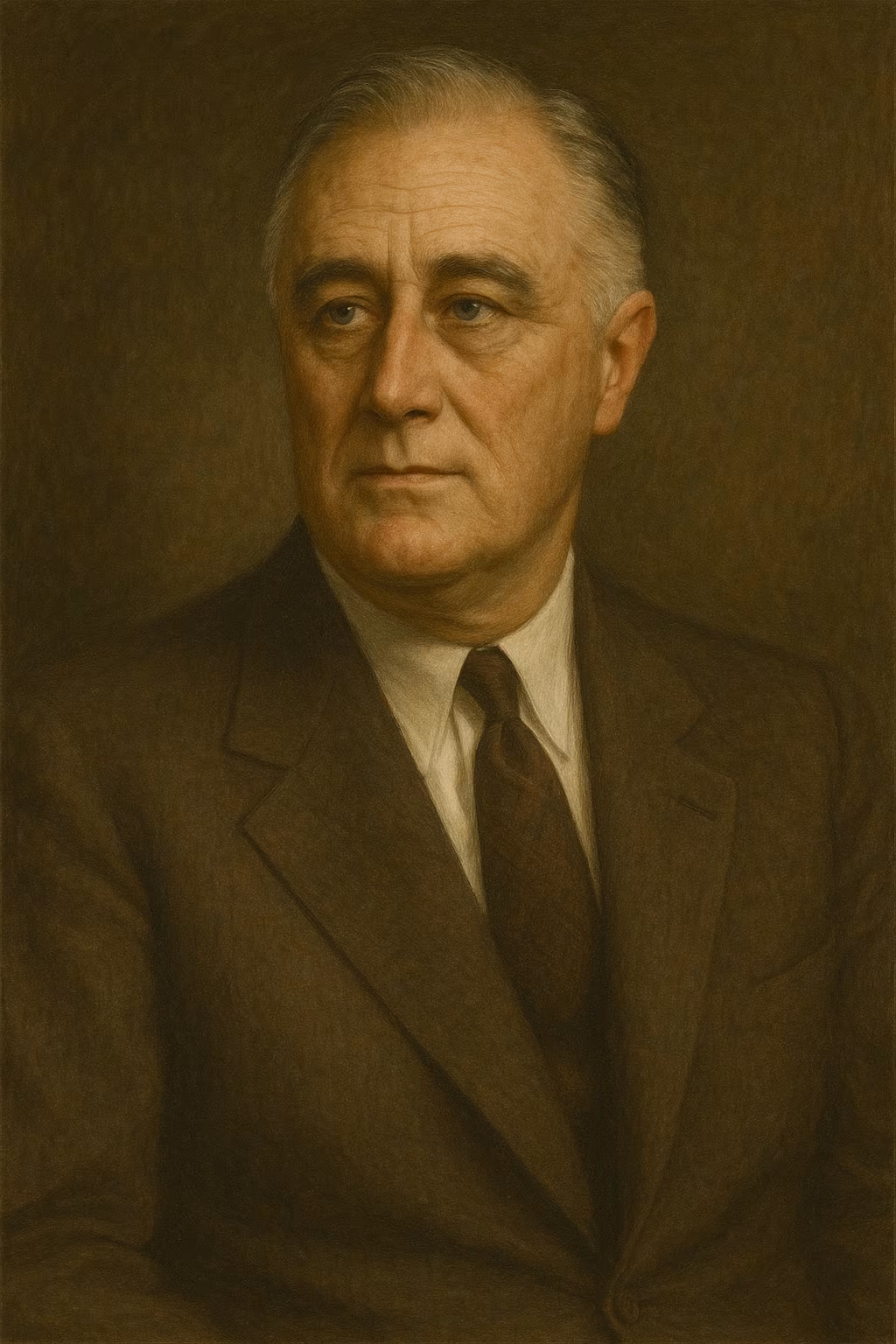

Franklin Delano Roosevelt

32nd President of the United States

Joan of Arc

French national heroine, saint, and military leader

Marie Curie

Physicist and Chemist (1867–1934)

Napoleon Bonaparte

General, First Consul and Emperor of the French

Specialized Sites

Batailles de France

Discover battles related to this figure

Dynasties Legacy

Coming soonExplore royal and noble lineages

Timeline France

Coming soonVisualize events on the chronological timeline