Victor Hugo (1802 – 1885)

Quick Summary

Victor Hugo (1802 – 1885) was a novelist and major figure in history. Born in Besançon, Doubs department, First French Empire, Victor Hugo left a lasting impact through Led the French Romantic revolution and reinvented the historical novel.

Birth

February 26, 1802 Besançon, Doubs department, First French Empire

Death

May 22, 1885 Paris, French Third Republic

Nationality

French

Occupations

Complete Biography

Origins And Childhood

Victor-Marie Hugo was born on 26 February 1802 in Besançon, the third son of Léopold-Sigisbert Hugo, an artillery officer promoted by Napoleon, and Sophie Trébuchet, a royalist from Nantes. His childhood oscillated between military postings with his father and the Parisian refuge of his mother, who hosted a royalist salon on Rue des Feuillantines. This split upbringing exposed him to the political fractures of post-revolutionary France. Travels to Italy, Spain, Corsica, and Lorraine fed his imagination with landscapes and languages later woven into his fiction. Educated at the Lycée Louis-le-Grand, he excelled in classical rhetoric and declared at fourteen, “I want to be Chateaubriand or nothing.” Mathematics for the École Polytechnique shared time with voracious reading of Virgil, Shakespeare, Corneille, and Ossian. After his parents separated, he remained with his mother, who encouraged his literary ambitions and tolerated his courtship of Adèle Foucher, whom he married in 1822. Early success came with the Royal Academy’s prize for his “Odes et poésies diverses,” announcing a young poet loyal to the Bourbon Restoration yet seeking an individual voice. The newlyweds faced financial uncertainty: Hugo co-founded the journal Le Conservateur littéraire with his brothers, translated Byron, and wrote serialized fiction. The death of his first child, Léopold, intensified his meditations on fate. Between 1823 and 1830 the family grew—Léopoldine, Charles, François-Victor, and Adèle—while their Paris apartment on Rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs became a meeting place for Romantic youth reading drafts of Han d’Islande, Bug-Jargal, and nascent dramas.

Historical Context

Hugo’s life spans a succession of French regimes: Consulate, Empire, Restoration, July Monarchy, Second Republic, Second Empire, and Third Republic. Each transition shaped his politics, shifting from maternal royalism to liberal, republican, and democratic convictions. The struggle between ultras and liberals in the 1820s, the rise of Romanticism after 1830, and the growth of a mass press provided the stage on which Hugo acted. After the 1848 revolution, social questions dominated public debate. Industrialization, Haussmann’s redesign of Paris, workers’ associations, and the June Days uprising sharpened Hugo’s awareness of inequality. Elected to the Constituent and then Legislative Assembly, he argued for universal suffrage, free secular education, and the end of capital punishment. The 1851 coup d’état and the subsequent Second Empire coincided with European nationalist movements and abolitionist campaigns; Hugo used his fame to support Poles, Italians, Greeks, Haitians, and Irish patriots. The Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune (1871) ushered in the Third Republic, and the elder statesman defended amnesty for communards while advocating “United States of Europe.” Living through these upheavals allowed Hugo to participate in debates over press freedom, secular schooling, and social welfare, leaving abundant speeches, petitions, and prefaces that testify to his evolving republicanism.

Public Ministry

Hugo’s literary “public ministry” began with royalist Odes (1822–1828), but his Romantic manifesto erupted with Cromwell’s preface (1827) and the theatrical shock of Hernani in 1830. Breaking classical rules, he mingled noble and popular registers, drawing crowds and sparking nightly riots at the Comédie-Française. He followed with Notre-Dame de Paris (1831), a Gothic revival novel; The Last Day of a Condemned Man (1832), a plea against the guillotine; and poetry collections such as Autumn Leaves and Songs of Twilight. Elected to the Académie française in 1841, he gathered around him artists like Delacroix and Berlioz and writers including Musset, Balzac, and Dumas. His works ranged from Romantic drama (Ruy Blas, Lucrezia Borgia) to social novels (Les Misérables, Les Travailleurs de la mer), prophetic epics (La Légende des siècles), and political satire (Les Châtiments). Prefaces served as manifestos defending artistic freedom and the moral purpose of literature. Hugo negotiated directly with publishers, protected authors’ rights in international congresses, and revised his manuscripts obsessively. Travels along the Rhine, in Brittany, and in Spain yielded sketchbooks and ethnographic notes. By embracing serial publication and staged readings, he forged a modern relationship between author, media, and mass audience.

Teachings And Message

Victor Hugo’s works unite compassion with prophetic rhetoric. He envisioned literature as a tool to expose misery, ignorance, and institutional injustice. The Hunchback of Notre-Dame advocated safeguarding Gothic heritage, while The Last Day of a Condemned Man and Claude Gueux confronted readers with the brutality of capital punishment. Les Misérables blended popular epic and Christian ethics, portraying redemption through love and labor in the figure of Jean Valjean. Poetry collections explored cosmic dualities. Les Contemplations (1856) mourned his daughter Léopoldine and meditated on memory and transcendence. Les Châtiments (1853) thundered against the Second Empire. La Légende des siècles (1859–1883) mapped humanity’s march toward liberty. Hugo believed literature should enlighten the people, describing writers as “lamps” guiding progress. He gave voice to the downtrodden—convicts, orphans, insurgents—asserting their dignity in elevated language. Politically, he argued for republican humanism: universal suffrage, free education, women’s property rights, and international solidarity. During the siege of Paris he opened his home to refugees and wrote L’Année terrible, chronicling war and the Commune. For Hugo, the writer functioned as moral conscience and advocate of the oppressed.

Activity In Galilee

Daily discipline anchored Hugo’s creative life. In Paris he rose before dawn, dictated chapters, and corrected proofs in coffee-stained margins. Notebooks recorded walks along the Seine, visits to prisons, and conversations with printers and reformers. He read to students, corresponded with liberal clergy, and observed crowds on the boulevards to capture speech rhythms. Exile on Jersey (1852–1855) and Guernsey (1855–1870) reshaped his routines. At Marine Terrace and later Hauteville House, he fashioned Oriental-inspired interiors and wrote facing the sea. He hosted fellow exiles, experimented with table-turning séances, and sketched fantastical landscapes. Juliette Drouet, his lifelong companion, copied manuscripts and managed his correspondence. From Guernsey emerged Les Contemplations, Les Misérables, Les Travailleurs de la mer, and L’Homme qui rit. Hugo drafted scenes on separate sheets pinned to walls, read British newspapers to track European politics, and donated royalties to disaster victims and schools. Appeals for Russian abolition of capital punishment and support for Italian unification show how exile became a laboratory for cosmopolitan activism.

Journey To Jerusalem

Hugo’s decisive confrontation with power began when President Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte drifted toward authoritarianism. His 1850 speech “Misère” denounced growing poverty; after the 2 December 1851 coup he helped organize resistance and fled to Brussels. The Second Empire banished him, censored his works, and barred his name from official lists. He retaliated with scathing pamphlets—Napoléon le Petit and Les Châtiments—and refused imperial amnesties, declaring, “When liberty returns, I shall return.” Expelled from Jersey in 1855, he settled in Guernsey, turning his home into a shrine for European dissidents. Only the fall of Napoleon III in 1870 brought him back to Paris, where crowds welcomed him as a hero. During the siege of Paris he joined the National Guard, published appeals for solidarity, and later advocated amnesty for the Commune insurgents despite disagreeing with their violence. His Senate speeches in the 1870s opposed capital punishment and defended urban poor, pitting him against conservative Catholics and monarchists. Hugo’s “journey to Jerusalem” thus symbolizes his moral confrontation with authoritarian power in the name of republican ideals.

Sources And Attestations

An extraordinary archival trail documents Hugo’s life. Complete editions by Hetzel and later Gallimard’s Pléiade compile novels, poems, plays, speeches, and letters. Travel notebooks, family journals (those of Juliette Drouet, Charles, and François-Victor), and memoirs from contemporaries such as Léon Gozlan and Théophile Gautier enrich the record. National Archives store his parliamentary dossiers and petitions; the Victor Hugo Houses in Paris and Guernsey preserve manuscripts, drawings, and furniture. Nineteenth-century newspapers—Le Moniteur universel, La Presse, Le Siècle, L’Illustration—tracked his publications, public readings, and anniversaries. Minutes from the Académie française and proceedings of international literary congresses document his advocacy for authors’ rights. His political speeches appear in the multi-volume Actes et Paroles. Photographs by Nadar and Étienne Carjat, as well as Daumier’s caricatures, capture his public image. Modern critical editions by Jean-Marc Hovasse, Guy Rosa, and others cross-reference these materials with family archives. More than 20,000 letters survive, revealing transnational networks of intellectuals and activists. Digitization projects by the Bibliothèque nationale de France and the ITEM make drafts and correspondence accessible to scholars and readers worldwide.

Historical Interpretations

Historians and critics from Sainte-Beuve to modern scholars have continually reassessed Hugo. Sainte-Beuve admired his imagination yet questioned his excess; Hippolyte Taine read him as the voice of democratic sensibility. Twentieth-century biographers—André Maurois, Jean Massin, Graham Robb—emphasized psychological and political dimensions. Structuralist and narratological approaches examined Hugo’s language and myth-making, while historians of the Third Republic analyzed the creation of the national cult surrounding him. Recent studies highlight the multiplicity of his commitments: social novels, political theater, metaphysical poetry, visionary drawing. Research centers such as the Institut des textes et manuscrits modernes use genetic criticism to reconstruct drafts of Les Misérables and La Légende des siècles. Postcolonial readings revisit his stances on Algeria and Haiti; gender-focused scholarship studies his portrayals of women and daughters. Contemporary performances—from Robert Hossein’s stadium productions to international adaptations of Les Misérables—continue to debate fidelity to Hugo’s texts and the universality of his message, keeping academic and popular conversations alive.

Legacy

Hugo’s death in 1885 prompted a national funeral; more than two million mourners accompanied his coffin from the Arc de Triomphe to the Panthéon. Streets, schools, and libraries around the world bear his name. His novels and poems circulate globally in translations, films, musicals, and illustrated editions. Characters such as Jean Valjean, Quasimodo, and Gavroche symbolize social justice, empathy for the marginalized, and youthful rebellion. Twentieth-century commemorations by UNESCO and the French state reaffirmed his universal stature. Campaigns for abolition of the death penalty, expanded education, and humanitarian aid often cite his writings. Poets and novelists worldwide—Pablo Neruda, Aimé Césaire, Léopold Sédar Senghor, Marguerite Yourcenar—acknowledge his influence. Hauteville House, restored in 2019, draws international visitors. Digital libraries like Gallica provide open access to his manuscripts, while educators employ his speeches to teach rhetoric and civic values. Hugo remains a touchstone for artists, activists, and policymakers convinced that literature can transform society.

Achievements and Legacy

Major Achievements

- Led the French Romantic revolution and reinvented the historical novel

- Used literature to popularize the fight against capital punishment and social injustice

- Defended the Republic, universal suffrage, and free education in Parliament

- Left a universal body of work translated worldwide

Historical Legacy

Victor Hugo embodies the power of language in service of emancipation. His novels, poems, and speeches continue to inspire popular culture, social movements, and educational policy worldwide. From Paris to Seoul, Mexico City to Dakar, his name remains synonymous with liberty, justice, and literary greatness.

Detailed Timeline

Major Events

Birth

Born in Besançon to a family split between royalist loyalty and Napoleonic service

Early Odes

Publishes Odes et poésies diverses and marries Adèle Foucher

Hernani

Stages Hernani, igniting the Romantic theatre revolution

The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

Releases the novel advocating Gothic heritage

Académie française

Elected to the French Academy

Parliamentary mandate

Serves in the Constituent and Legislative Assemblies of the Second Republic

Exile

Leaves France after Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte’s coup

Les Misérables

Publishes the social novel that becomes a global success

Return

Returns to Paris after the fall of the Second Empire

State funeral

Dies in Paris and receives a national funeral at the Panthéon

Geographic Timeline

Famous Quotes

"Those who live are those who fight."

"Freedom begins where ignorance ends."

"Opening a school means closing a prison."

External Links

Frequently Asked Questions

When was Victor Hugo born and when did he die?

Victor Hugo was born on 26 February 1802 in Besançon and died on 22 May 1885 in Paris after a short bout of pneumonia.

What are his major works?

His most famous works include Les Misérables, The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, Les Contemplations, Les Châtiments, Hernani, and Ruy Blas.

Why did Victor Hugo go into exile?

He opposed the 2 December 1851 coup d’état of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, refused to swear loyalty to the Empire, and took refuge in Brussels before settling in the Channel Islands until 1870.

What political causes did he support?

Hugo campaigned for press freedom, free secular education, universal suffrage, abolition of the death penalty, and national self-determination.

Where can his archives be consulted?

His manuscripts, correspondence, and drawings are preserved at the French National Archives, the Victor Hugo Houses in Paris and Guernsey, and the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Sources and Bibliography

Primary Sources

- Victor Hugo – Actes et Paroles

- Victor Hugo – Correspondance générale

- Victor Hugo – Les Misérables

- Victor Hugo – Les Contemplations

Secondary Sources

- Jean-Marc Hovasse – Victor Hugo ISBN: 9782251442849

- Graham Robb – Victor Hugo ISBN: 9780330491889

- Pierre Laforgue – Victor Hugo : l’épopée de la misère ISBN: 9782251432758

- Laure Murat – Victorine et les misérables ISBN: 9782072960355

External References

See Also

Related Figures

Charles de Gaulle

Leader of Free France and founding president of the Fifth Republic

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

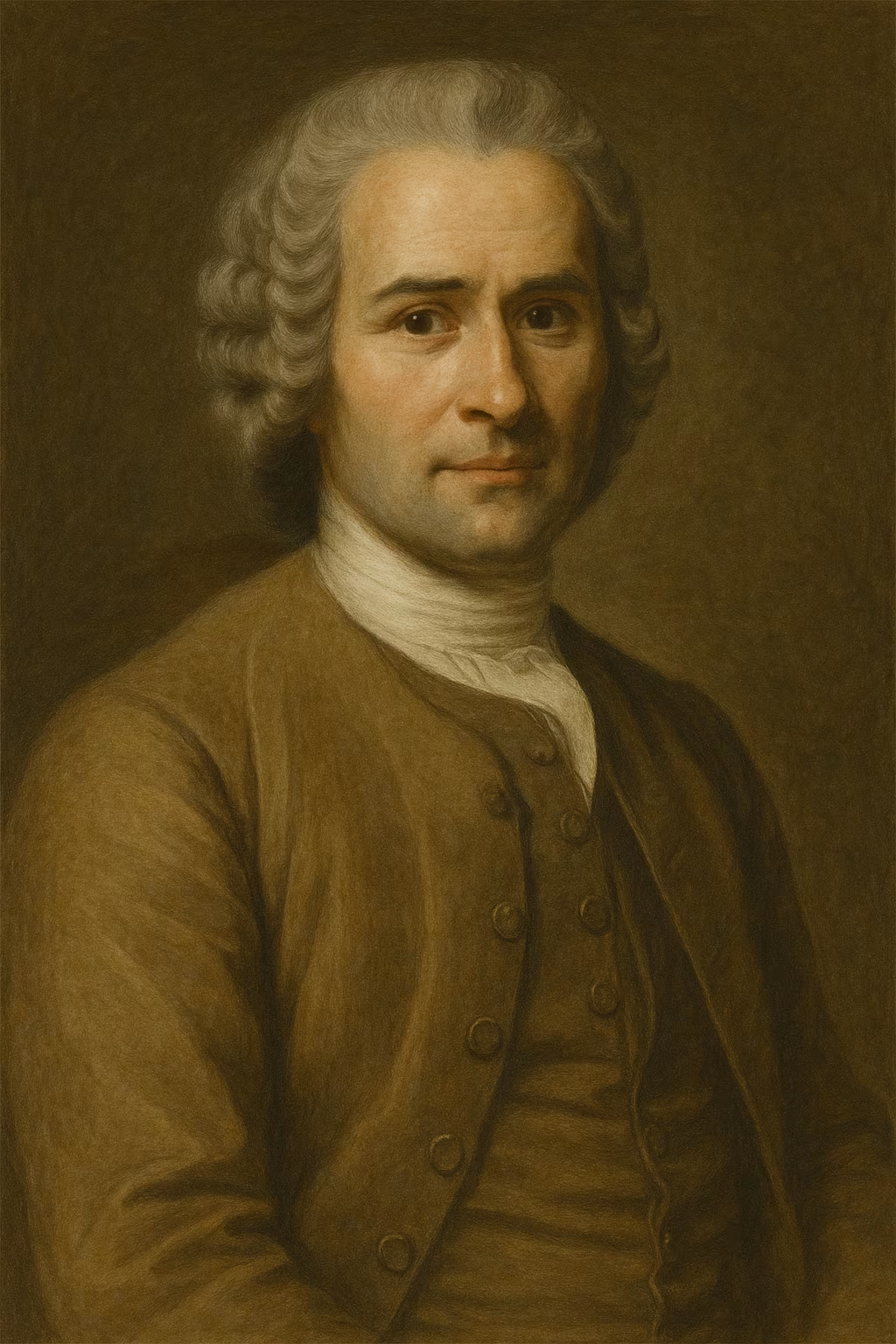

Philosopher, writer, and political theorist of the Enlightenment

Marie Curie

Physicist and Chemist (1867–1934)

Napoleon Bonaparte

General, First Consul and Emperor of the French

Specialized Sites

Batailles de France

Discover battles related to this figure

Dynasties Legacy

Coming soonExplore royal and noble lineages

Timeline France

Coming soonVisualize events on the chronological timeline