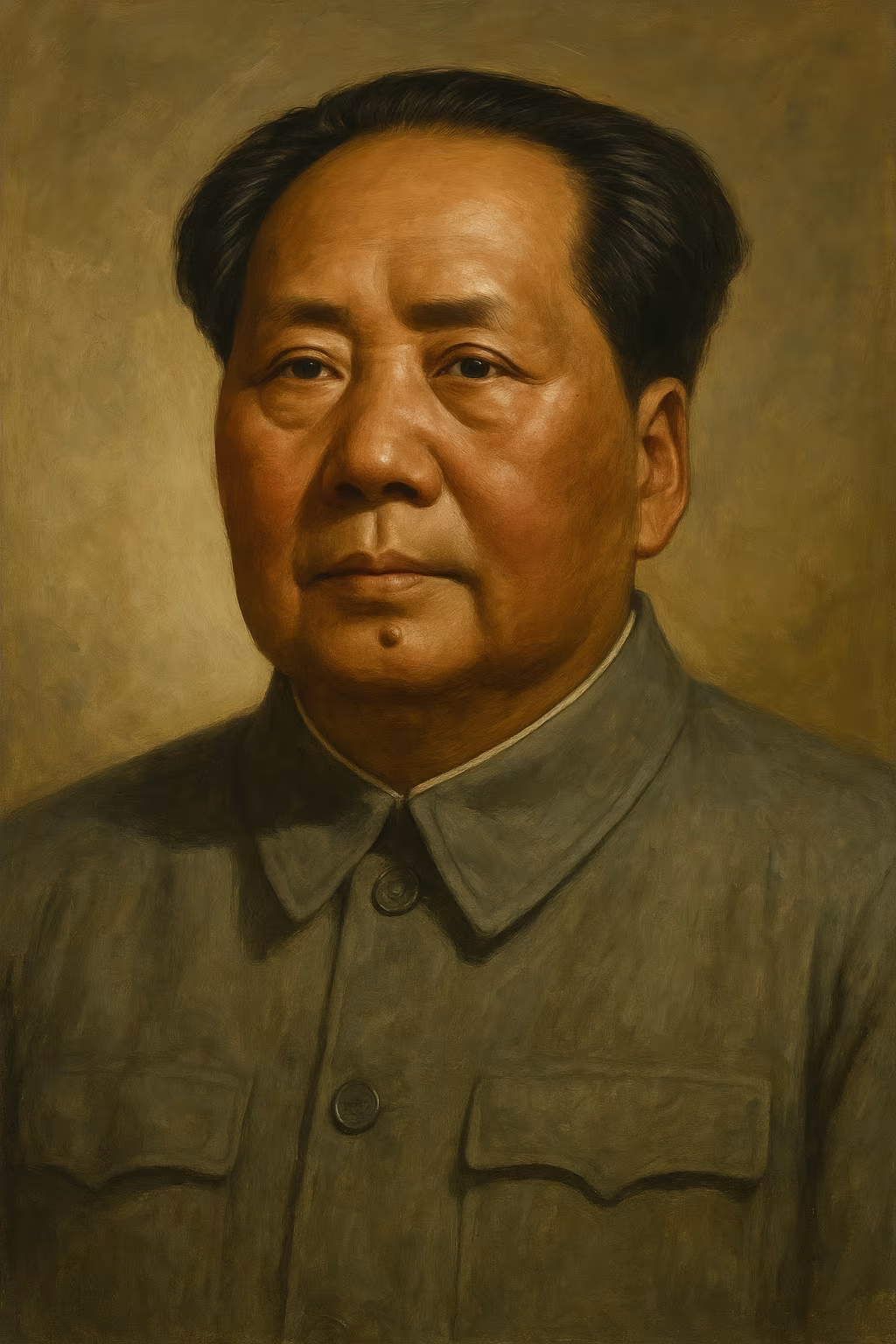

Mao Zedong (1893 – 1976)

Quick Summary

Mao Zedong (1893 – 1976) was a revolutionary and major figure in history. Born in Shaoshan, Hunan, Qing Empire, Mao Zedong left a lasting impact through Commanded the Long March and secured CCP leadership.

Birth

December 26, 1893 Shaoshan, Hunan, Qing Empire

Death

September 9, 1976 Beijing, People’s Republic of China

Nationality

Chinese

Occupations

Complete Biography

Origins And Childhood

Born on 26 December 1893 in Shaoshan, Hunan, Mao Zedong grew up in a relatively prosperous peasant household. His father, Mao Yichang, was a strict disciplinarian who had served in the Qing army before becoming a landholder, while his mother, Wen Qimei, practiced Buddhism and encouraged compassion. Mao’s early education followed classical Confucian curricula, but the 1911 Revolution redirected him toward modern schooling at the Changsha normal college. Brief military service with local republican units during the fall of the Qing dynasty, coupled with exposure to radical journals, convinced Mao that China’s renewal demanded sweeping social change. In 1918 he worked in the library of Peking University under Li Dazhao, immersing himself in Marxist literature amid the ferment of the May Fourth Movement. Study groups he organized discussed women’s emancipation, science, and peasant rights. Returning to Hunan, Mao founded radical journals, organized trade unions, and married Yang Kaihui, a fellow activist. When the Chinese Communist Party convened its first congress in Shanghai in 1921, Mao participated as one of thirteen delegates and championed the idea that China’s revolution must draw strength from the countryside.

Historical Context

Early twentieth-century China was marked by political fragmentation, foreign intervention, and debates over modernization. After the 1911 Revolution, warlords carved up territories while the Nationalist Party (Guomindang) tried to rebuild state authority. The May Fourth protests of 1919 galvanized intellectuals who turned to Marxism, anarchism, and liberalism in search of solutions. Soviet advisors urged cooperation between the CCP and the Guomindang during the 1920s, but Chiang Kai-shek’s anti-communist purge in 1927 forced the Communists into rural bases, inaugurating a protracted civil war. Japanese expansion into Manchuria in 1931 and the full invasion of China in 1937 compelled a fragile united front even as the CCP developed independent rural strongholds. Mao’s theories of encircling the cities from the countryside, mass line mobilization, and protracted people’s war emerged from this period of dual pressures—Nationalist encirclement campaigns and foreign invasion.

Public Ministry

Mao consolidated leadership by transforming peasant unrest into revolutionary warfare. After failed urban uprisings, he retreated to the Jinggangshan mountains with Zhu De, experimenting with soviet-style governance and radical land redistribution. His 1927 “Report on an Investigation of the Peasant Movement in Hunan” argued that the peasantry could spearhead social revolution. Successive Nationalist campaigns forced the Communists on the Long March (1934-1935), a grueling trek that culminated in the Zunyi Conference, where Mao sidelined Comintern-aligned leaders and established strategic authority. At Yan’an, Mao launched cadre schools, cultural programs, and the rectification movement to instill ideological discipline. During the Anti-Japanese War, the Eighth Route Army and New Fourth Army expanded CCP influence through guerrilla warfare and land reform. By 1945 the Party counted nearly a million members. Negotiations with Chiang Kai-shek failed, and renewed civil war (1946-1949) saw Mao’s commanders win decisive campaigns—Liaoshen, Huaihai, Pingjin—that opened the path to Beijing and nationwide control.

Teachings And Message

Mao’s writings fused Marxism-Leninism with Chinese realities. Essays such as “On Practice” and “On Contradiction” (1937) emphasized dialectical analysis rooted in empirical investigation. The mass line called on cadres to learn from the people before providing leadership. Mao preached self-reliance, anti-imperialism, and continual revolution to prevent bureaucratic stagnation. Once in power, mass campaigns promoted literacy, collectivism, and ideological conformity. The Little Red Book distilled slogans about class struggle, egalitarianism, and devotion to the Party. Mao demanded austerity from officials yet tolerated the personal cult that elevated him as the embodiment of revolutionary virtue.

Activity In Galilee

From 1949 to 1956 the People’s Republic implemented sweeping reforms under Mao’s guidance. Land reform redistributed holdings to hundreds of millions of peasants, while campaigns against counterrevolutionaries dismantled the old elite. The First Five-Year Plan, backed by Soviet assistance, built heavy industry and collectivized agriculture through mutual-aid teams and cooperatives. The Hundred Flowers Campaign briefly encouraged intellectual criticism in 1956, but the subsequent Anti-Rightist Campaign silenced dissent. The Great Leap Forward (1958-1961) attempted to leapfrog industrial output via people’s communes and backyard furnaces. Administrative overreach, inflated production quotas, and poor harvests produced a devastating famine that killed tens of millions, prompting Mao to cede day-to-day management to Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping for a time.

Journey To Jerusalem

Mao soon reasserted dominance. The Socialist Education Movement (1963-1965) targeted corruption in the countryside, paving the way for the Cultural Revolution launched in 1966. Red Guards, inspired by Mao’s call to rebel, attacked perceived bourgeois elements, sparking factional violence and upheaval across the country. The People’s Liberation Army intervened from 1968 to restore order, yet political purges, labor disruptions, and military control reshaped society. Internationally, Mao broke with the Soviet Union, leading to border clashes in 1969, and orchestrated a strategic opening to the United States with Richard Nixon’s 1972 visit. The fall of Lin Biao in 1971 and the rivalry between Zhou Enlai’s pragmatic allies and Jiang Qing’s radical faction defined Mao’s final years. He died on 9 September 1976, shortly before the arrest of the Gang of Four, which effectively ended the Cultural Revolution.

Sources And Attestations

Research on Mao draws on CCP plenary records, official directives collected in the Selected Works and Manuscripts of Mao Zedong, and a growing body of declassified party and security archives. Memoirs by insiders—such as Li Zhisui’s account as Mao’s personal physician—and testimonies from former Red Guards supplement the record. Demographic data sets help quantify famine mortality, while foreign diplomatic cables from Moscow, Washington, London, and Paris provide external perspectives. Provincial archives opened since the 1990s enable historians to compare local experiences with central directives.

Historical Interpretations

Post-Mao Chinese historiography, framed by the 1981 party resolution, portrays Mao as a revolutionary founder whose contributions coexist with grave mistakes. Western biographers like Philip Short and Ross Terrill examine his charisma and ruthlessness, whereas scholars such as Roderick MacFarquhar, Michael Schoenhals, and Frank Dikötter emphasize the human toll of his campaigns. Others, including Arif Dirlik, situate Mao within global anti-imperialist movements, noting his influence across the Global South. Debates continue inside China, where neo-Maoists celebrate egalitarian ideals while liberals condemn the authoritarian legacy.

Legacy

Mao’s rule secured Chinese sovereignty, expanded literacy, advanced women’s rights, and built core industries, but also entrenched a coercive party-state, normalized mass campaigns, and precipitated disasters like the Great Leap famine and the Cultural Revolution. Abroad, Maoism energized revolutionary movements from Southeast Asia to Latin America. Post-1978 reforms under Deng Xiaoping rejected collectivized economics yet retained Mao’s symbolic stature—his portrait still dominates Tiananmen Square, embodying both national pride and contested memory.

Achievements and Legacy

Major Achievements

- Commanded the Long March and secured CCP leadership

- Proclaimed the People’s Republic of China on 1 October 1949

- Mobilized peasant-based land reform and mass campaigns

- Formulated Mao Zedong Thought with global revolutionary influence

Historical Legacy

Mao Zedong left China sovereign, industrializing, and mobilized, yet scarred by famine, ideological campaigns, and entrenched authoritarian control. His image continues to legitimize the Communist Party domestically and inspires revolutionary movements abroad despite enduring controversies over human costs.

Detailed Timeline

Major Events

Birth

Born in Shaoshan, Hunan

Founding Congress of the CCP

Participated as a delegate in Shanghai

Zunyi Conference

Consolidated strategic leadership during the Long March

PRC Proclaimed

Announced the People’s Republic of China from Tian’anmen

Great Leap Forward

Launched people’s communes and accelerated industrialization

Cultural Revolution

Mobilized Red Guards to purge the Party

Death

Died in Beijing after nearly three decades in power

Geographic Timeline

Famous Quotes

"A single spark can start a prairie fire."

"Serve the people."

"A revolution is not a dinner party."

External Links

Frequently Asked Questions

When did Mao Zedong lead China?

He emerged as the dominant figure in the Chinese Communist Party during the mid-1930s and chaired the People’s Republic of China from 1949 until his death in 1976.

What was Mao’s role in the Long March?

During the 1934-1935 Long March he secured strategic leadership at the Zunyi Conference, steering the Communists toward rural guerrilla warfare and eventual survival in Yan’an.

What impact did the Great Leap Forward have?

The campaign to collectivize agriculture and boost steel production triggered a catastrophic famine between 1959 and 1961, causing tens of millions of deaths and weakening Mao’s immediate authority.

Why did Mao launch the Cultural Revolution?

He sought to purge perceived revisionists, reignite revolutionary fervor, and prevent bureaucratic elites from steering China toward a Soviet-style path, leading to nationwide upheaval beginning in 1966.

How do historians assess Mao’s legacy?

Assessments balance achievements in unifying and transforming China against the massive human costs of his campaigns, producing divergent narratives in both Chinese and international scholarship.

Sources and Bibliography

Primary Sources

- Mao Zedong, Rapport sur l’enquête paysanne du Hunan (1927)

- Discours du 1er octobre 1949 – Proclamation de la République populaire de Chine

- Résolution du Comité central sur certaines questions de l’histoire de notre parti (1945)

- Résolution sur certaines questions de l’histoire du Parti depuis 1949 (1981)

- Quotidien du peuple – Campagne de la Révolution culturelle (1966-1969)

Secondary Sources

- Philip Short – Mao: A Life ISBN: 9780712666837

- Roderick MacFarquhar et Michael Schoenhals – Mao’s Last Revolution ISBN: 9780674027480

- Frank Dikötter – Mao’s Great Famine ISBN: 9780802779233

- Odd Arne Westad – Decisive Encounters: The Chinese Civil War, 1946-1950 ISBN: 9780804744840

- Jung Chang et Jon Halliday – Mao: The Unknown Story ISBN: 9780099460797

External References

See Also

Specialized Sites

Batailles de France

Discover battles related to this figure

Dynasties Legacy

Coming soonExplore royal and noble lineages

Timeline France

Coming soonVisualize events on the chronological timeline