Émilie du Châtelet (1706 – 1749)

Quick Summary

Émilie du Châtelet (1706 – 1749) was a mathematician and major figure in history. Born in Paris, Kingdom of France, Émilie du Châtelet left a lasting impact through Annotated translation of Newton’s Principia Mathematica.

Birth

December 17, 1706 Paris, Kingdom of France

Death

September 10, 1749 Lunéville, Duchy of Lorraine

Nationality

French

Occupations

Complete Biography

Origins And Childhood

Born into the Parisian aristocracy, Gabrielle Émilie Le Tonnelier de Breteuil grew up in the family hôtel on the rue Traversière in the Faubourg Saint-Honoré. Her father, Louis Nicolas Le Tonnelier de Breteuil, master of ceremonies for foreign envoys, encouraged her interest in languages and science. Her mother, Gabrielle Anne de Froullay, emphasized courtly etiquette, confronting Émilie with the dual expectations of noble decorum and scholarly ambition. Tutors introduced her to Latin, Italian, and German; she visited the Académie Royale de Musique and devoured the comedies of Molière. As a teenager she showed unusual aptitude for mental calculation and philosophical debate. Her father enlisted mathematician Pierre Varignon and later the Swiss scholar Samuel König to solidify her training in geometry and physics. She practiced fencing and riding—activities rare for young women of her rank—and developed the assurance that would define her intellectual style: audacity, rigor, and delight in controversy.

Historical Context

Early eighteenth-century France experienced the Regency and the personal rule of Louis XV. Parisian salons became hubs of intellectual sociability where Cartesian, Lockean, and Newtonian ideas circulated. Scientific institutions such as the Académie des Sciences remained closed to women. Debates over infinitesimals, vis viva, and gravitational theory polarized savants, while the Enlightenment fostered a transnational exchange of letters and publications. The War of the Spanish Succession, the War of the Polish Succession, colonial ventures, and industrial innovations formed the geopolitical backdrop in which du Châtelet shaped her thought. Experimental programs led by Réaumur and Musschenbroek informed her scientific reading.

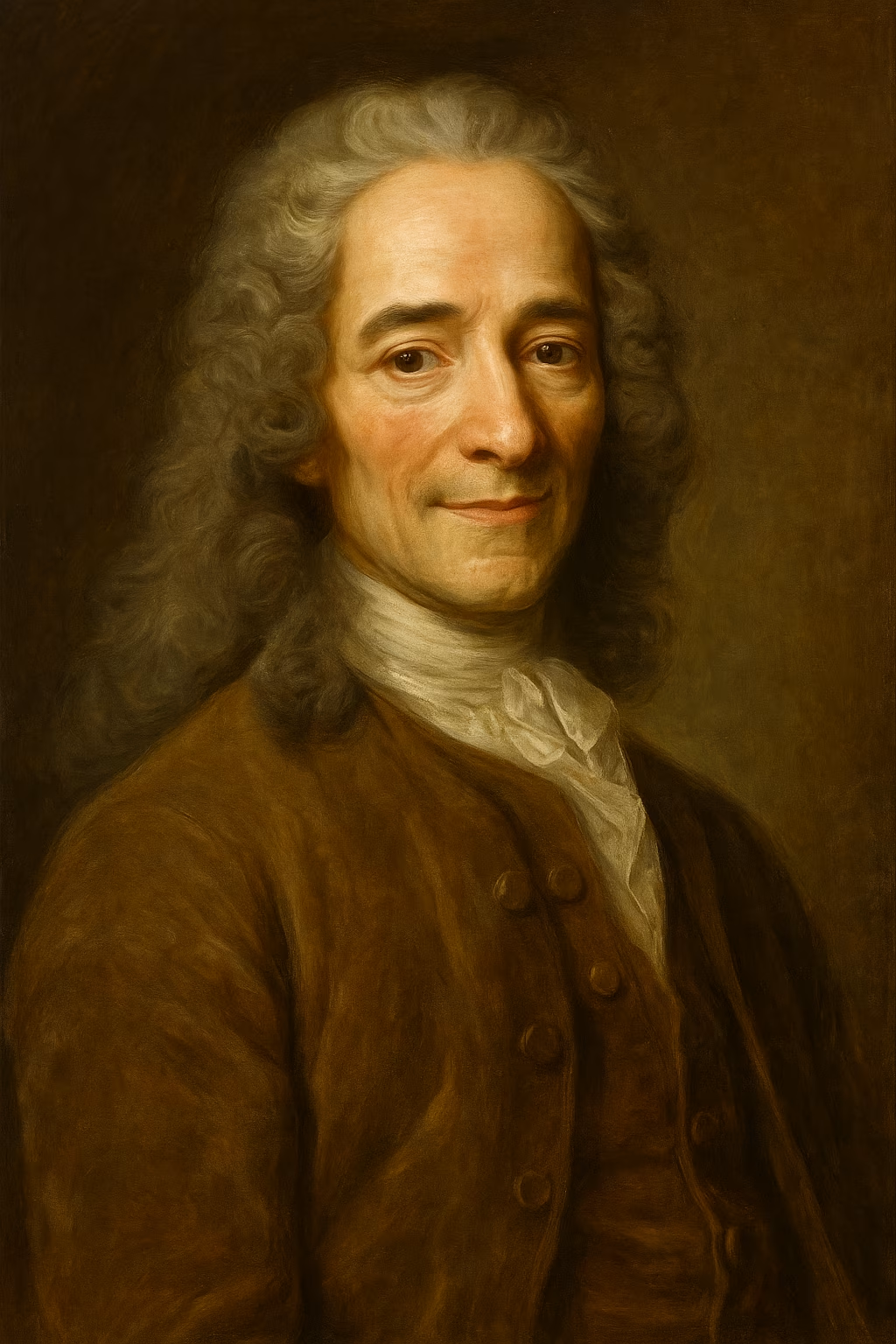

Public Ministry

Married in 1725 to Marquis Florent-Claude du Châtelet-Lomont, Émilie settled at the family estate of Cirey-sur-Blaise. Far from Paris, she transformed the château into a laboratory and library, outfitting a physics cabinet with Dutch and English instruments. Her meeting with Voltaire in 1733 sealed an intellectual and romantic partnership: the philosopher took refuge at Cirey, where the two scholars conducted experiments on light and heat, commented on Newton’s writings, and embarked on an ambitious program of mathematical study. Du Châtelet attended lessons with Alexis Clairaut, a prodigy of the Académie, to deepen her command of calculus. She corresponded with Pierre-Louis Moreau de Maupertuis on vis viva, engaged Cartesian opponents, and entered competitions at the Académie des Sciences. Her 1738 Discourse on Happiness linked ethics, reason, and earthly felicity, while her 1740 Foundations of Physics presented a Newton-Leibniz synthesis for educated readers.

Teachings And Message

In Foundations of Physics, du Châtelet sought to render the principles of modern science accessible by combining mathematical exposition with philosophical reflection. She defended the Leibnizian notion of vis viva (mv²) over the Cartesian quantity of motion (mv), anticipating later debates over kinetic energy. Her approach stressed the union of experiment and reason, the distinction between working hypotheses and demonstrated truths, and the legitimacy of final causes in the natural order. Her correspondence reveals acute awareness of women’s intellectual constraints. She argued for an education beyond polite accomplishments, insisted that genius had no gender, and challenged the claim that sensitivity was incompatible with scientific rigor. Her message, rooted in Enlightenment moral philosophy, celebrated intellectual autonomy, the pursuit of happiness through study, and the civic responsibility of scholars.

Activity In Galilee

Du Châtelet travelled widely to connect with Europe’s scientific community. In 1735 and 1736 she frequented the Paris salons of Madame de Tencin and Madame Geoffrin, debating with Fontenelle, Montesquieu, and d’Alembert. She visited the Brussels Academy and corresponded with mathematician Johann Bernoulli. In 1737 she and Voltaire shared the Rouen Academy prize for a memoir on the nature of fire, demonstrating mastery of experimental method. Her itineraries brought her to Lunéville, court of King Stanisław Leszczyński; to Paris, where she oversaw the printing of her works; and to The Hague, where she acquired precision scientific instruments. This mobility strengthened her intellectual network and helped disseminate Newtonian theory in French.

Journey To Jerusalem

Between 1745 and 1749 her activity intensified despite institutional obstacles. The Académie des Sciences refused to hear her papers publicly because she was a woman, and critics mocked her partnership with Voltaire. Du Châtelet replied in print: she drafted Reflections on Newton’s Metaphysics, answered Jean-Jacques Dortous de Mairan on vis viva, and continued to reconcile Leibniz with Newton. In 1746 she undertook the full translation of the Principia Mathematica. Working through the night, often with Clairaut’s assistance, she verified the calculations. Her 1749 pregnancy by poet Jean-François de Saint-Lambert caused scandal and endangered her health. Despite social pressure and exhaustion, she corrected proofs of her translation until her final hours.

Sources And Attestations

Evidence for du Châtelet’s life comes from her correspondence, Voltaire’s memoirs, Académie des Sciences records, and parish registers from Paris and Lunéville. Manuscripts preserved at the Bibliothèque nationale de France—including drafts of the Principia translation—reveal her working methods. Contemporary observers such as Madame de Graffigny, Marquis d’Argenson, and Jean-François de Saint-Lambert confirmed her reputation as a passionate, independent scholar. Posthumous editions of Foundations of Physics (1740, 1742) and her Philosophical Letters, along with reviews by the Académie Royale des Sciences and the Royal Society, trace the reception of her work. Modern historians—Judith P. Zinsser, Elisabeth Badinter, Nina Rattner Gelbart—have reassessed her contributions by combining manuscript evidence with printed sources.

Historical Interpretations

From the eighteenth through the nineteenth century, du Châtelet’s image alternated between Voltaire’s muse and a brilliant mathematician. Romantic critics sometimes reduced her to an inspirer, but twentieth-century scholarship restored the depth of her scientific thought. Robert Locqueneux’s studies of Newtonian diffusion, Judith P. Zinsser’s intellectual biography, and Paola Bertucci’s research on women in experimentation demonstrate the originality of her physics. Historians of science now highlight her role in formalizing energy, her early grasp of calculus’s importance, and her integration of rational philosophy with experimental practice. Feminist scholars view her as a pioneer of women’s participation in STEM fields, expanding her legacy beyond translation alone.

Legacy

Her annotated translation of the Principia, published in 1756 thanks to Clairaut and astronomer Lalande, became the French-language standard for astronomy and celestial mechanics into the nineteenth century. Her explanatory notes on integral calculus, dynamics, and gravitation offered vital pedagogical tools for engineers and astronomers. Discourse on Happiness influenced later Enlightenment moral reflection, while her advocacy for girls’ education inspired Condorcet, Olympe de Gouges, and nineteenth-century feminists. In the history of science, du Châtelet stands among the figures who naturalized Newtonian physics on the continent. Schools, laboratories, and scientific prizes bear her name, and her thought continues to inform debates on women’s place in science and on the alignment of mathematical rigor with the philosophy of happiness.

Achievements and Legacy

Major Achievements

- Annotated translation of Newton’s Principia Mathematica

- Defense and clarification of the concept of vis viva

- Creation of a scientific laboratory at Cirey-sur-Blaise

- Advocacy for women’s scientific education

Historical Legacy

A major Enlightenment scholar, du Châtelet introduced Newtonian physics to France, blended mathematics with moral philosophy, and opened pathways for women in science. Her work continues to illuminate the diffusion of scientific ideas and the quest for female intellectual autonomy.

Detailed Timeline

Major Events

Birth

Born in Paris to the Le Tonnelier de Breteuil family

Marriage

Married Marquis Florent-Claude du Châtelet-Lomont

Cirey collaboration

Scientific partnership with Voltaire begins

Foundations of Physics

Published Institutions de physique

Principia translation

Undertook annotated translation of Newton’s Principia

Death

Died in Lunéville after completing the translation

Geographic Timeline

Famous Quotes

"Happiness must be the work of reason."

"I was born to oppose all that surrounds me with a free and independent mind."

"Study is the only means to make our life bearable without boredom."

External Links

Frequently Asked Questions

When was Émilie du Châtelet born and when did she die?

She was born on 17 December 1706 in Paris and died on 10 September 1749 in Lunéville, shortly after giving birth to a daughter.

What is her most famous work?

Her annotated French translation of Isaac Newton’s Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica, completed in 1749 and published in 1756, is her landmark contribution.

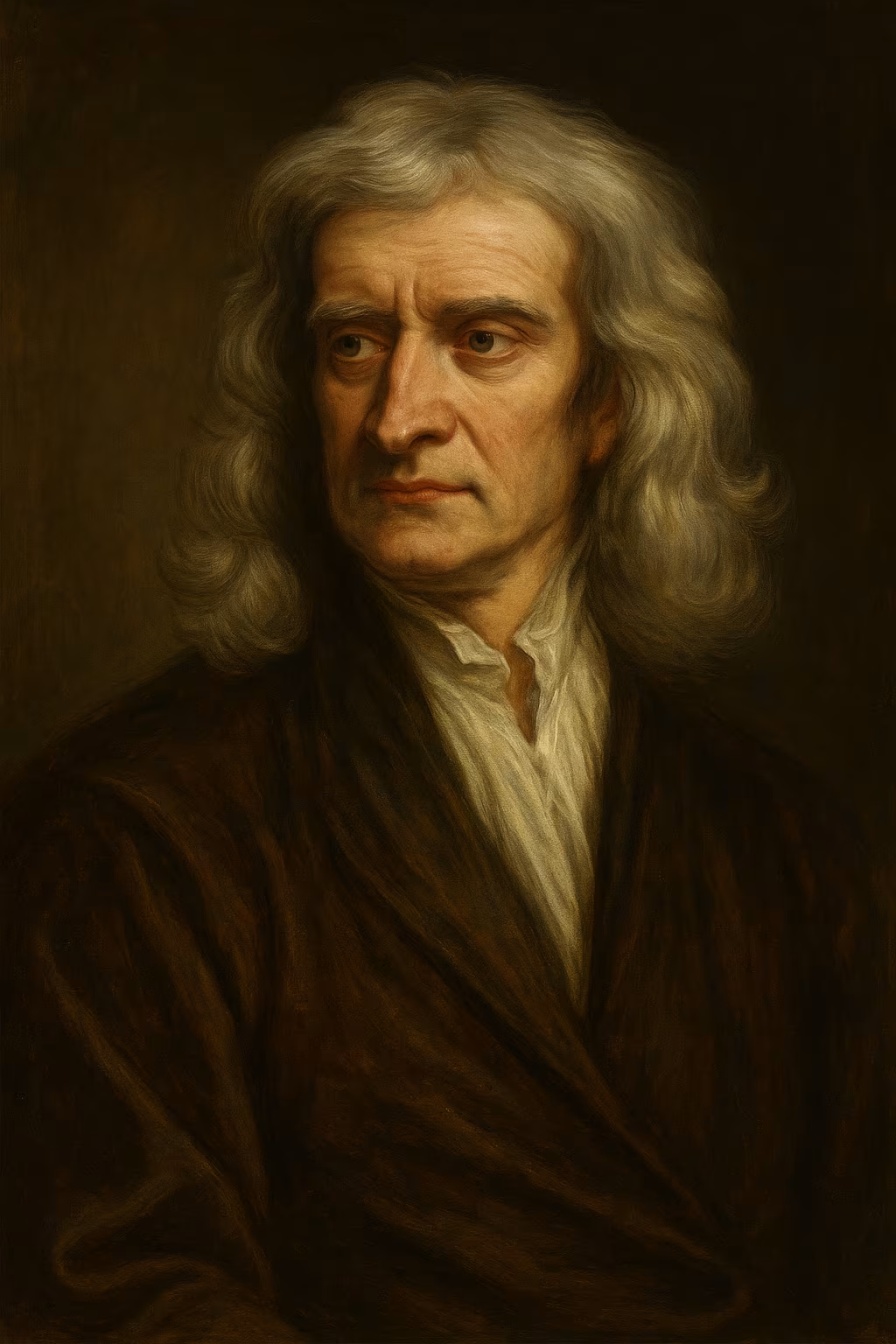

Which scientists influenced her?

She drew on Newton, Leibniz, and the Bernoulli family, and corresponded with Maupertuis, Clairaut, and Euler.

What were her research areas?

Rational mechanics, Newtonian physics, natural philosophy, metaphysics, and applied mathematics.

Why is Émilie du Châtelet important for women’s history?

She demonstrated that women could excel in the exact sciences, advocated female education, and provided a model celebrated by Enlightenment philosophers and nineteenth-century feminists.

Sources and Bibliography

Primary Sources

- Émilie du Châtelet — Institutions de physique (1740)

- Émilie du Châtelet — Discours sur le bonheur (1779)

- Voltaire — Correspondance avec Émilie du Châtelet

- Clairaut — Lettres sur la traduction des Principia

Secondary Sources

- Judith P. Zinsser — La Dame d’esprit: A Biography of the Marquise du Châtelet ISBN: 9780674013255

- Elisabeth Badinter — Émilie, Émilie: L’Ambition féminine au XVIIIe siècle ISBN: 9782251443439

- Nina Rattner Gelbart — Feminine and Opposition Journalism in Old Regime France ISBN: 9780520076764

- Robert Locqueneux — La Diffusion du newtonianisme en France (2008) ISBN: 9782745316114

- Paola Bertucci — Artisanal Enlightenment: Science and the Mechanical Arts in Old Regime France ISBN: 9780300238631

- Danielle Maira — Émilie du Châtelet and the Newtonian Legacy ISBN: 9783030143120

External References

See Also

Related Figures

Specialized Sites

Batailles de France

Discover battles related to this figure

Dynasties Legacy

Coming soonExplore royal and noble lineages

Timeline France

Coming soonVisualize events on the chronological timeline