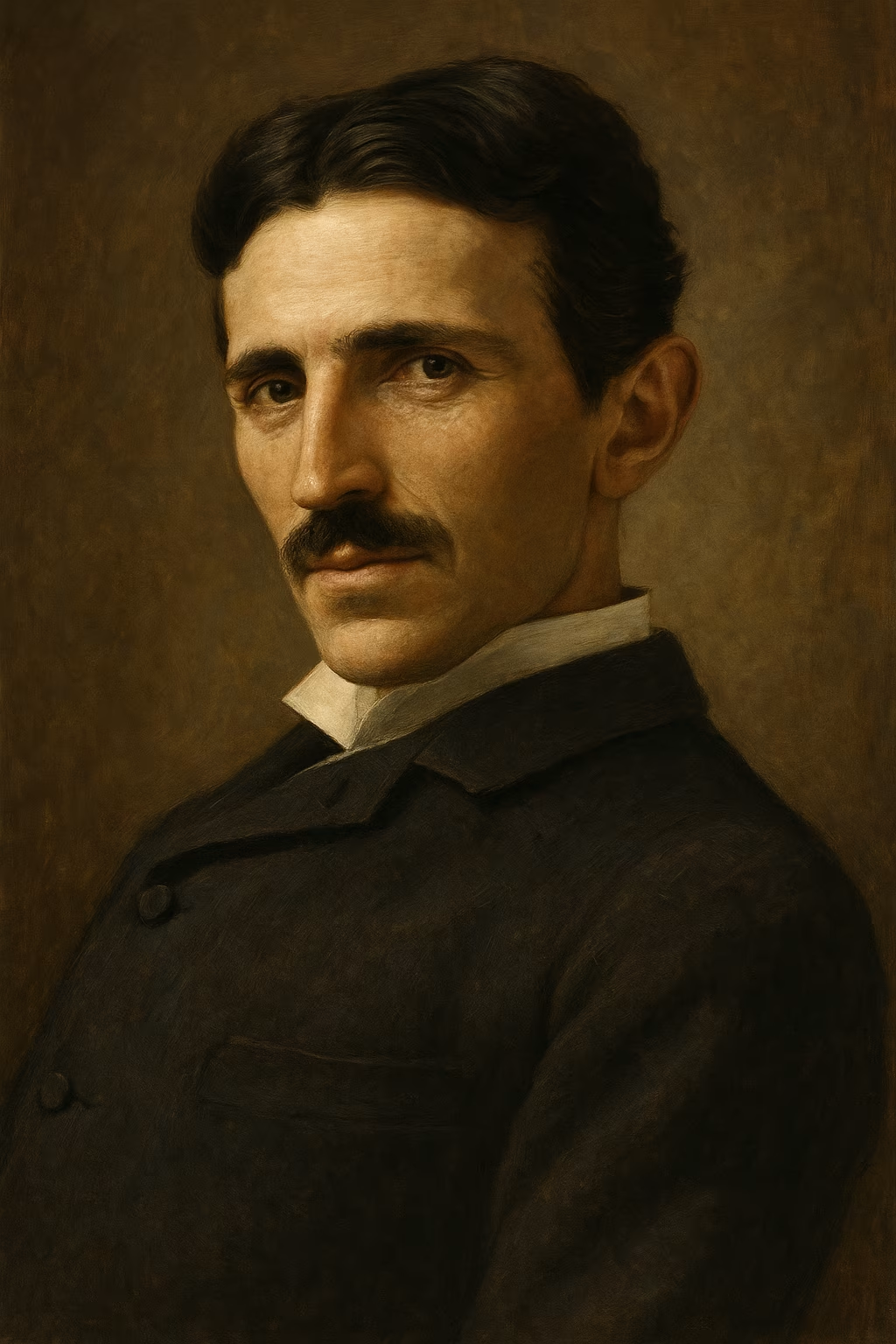

Nikola Tesla (1856 – 1943)

Quick Summary

Nikola Tesla (1856 – 1943) was a inventor and major figure in history. Born in Smiljan, Austrian Empire (modern Croatia), Nikola Tesla left a lasting impact through Designed the polyphase induction motor and alternating-current distribution system.

Birth

July 10, 1856 Smiljan, Austrian Empire (modern Croatia)

Death

January 7, 1943 New York, United States

Nationality

Serbian-American

Occupations

Complete Biography

Origins And Childhood

Nikola Tesla was born into a Serbian Orthodox family in the Military Frontier of the Austrian Empire, where border regiments and clergy shaped local life. His father Milutin, a priest, cultivated rhetoric and literature, while his mother Đuka, renowned for crafting household devices, nurtured his mechanical creativity. Tesla’s eidetic memory and vivid imagination, often attributed to reciting biblical passages and epic poetry, emerged in early childhood. A severe electrical shock from farm equipment during adolescence deepened his fascination with electromagnetism. At schools in Gospić and Karlovac he excelled in mathematics and physics, devouring treatises by Helmholtz and Faraday. A cholera epidemic in 1874 nearly killed him; promising his father he would become an engineer rather than enter the clergy, he resumed his studies with renewed determination. Tesla enrolled at the Imperial-Royal Technical College in Graz, attending lectures on the Gramme dynamo and questioning the waste inherent in mechanical commutators. Although financial hardship prevented him from graduating formally, professors praised his ability to perform complex engineering calculations mentally. A brief stay in Prague in 1880 exposed him to natural philosophy courses before he joined the Central Telegraph Office in Budapest, where telephony challenges revealed the practical limits of existing systems. These formative years also honed his linguistic and artistic sensibilities: Tesla spoke several languages, played the violin, and loved Serbian poetry, blending cultural refinement with scientific rigor. This synthesis shaped an inventor capable of envisioning whole systems and articulating their societal impact long before prototypes reached the workshop.

Historical Context

Tesla’s upbringing unfolded amid the second industrial revolution, as electrification began to eclipse steam power. The multiethnic Austro-Hungarian Empire sought modernization to keep pace with Western Europe, while the United States invested heavily in telegraphy and lighting. Discoveries by Ørsted, Faraday, and Maxwell had established electromagnetic theory, yet practical deployment lagged: most cities still relied on direct current grids limited to a few city blocks. Demand for street lighting, elevators, streetcars, and long-distance telephony created a global race for efficient, scalable electrical systems. Patents and venture capital became strategic instruments. American financiers like George Westinghouse and J. P. Morgan funded private laboratories, expecting defensible intellectual property. International exhibitions—Vienna 1873, Paris 1889, Chicago 1893—served as theaters where inventors displayed innovations to worldwide audiences. Engineers circulated across continents; Tesla collaborated with telephony firms in Budapest, Edison affiliates in Paris, and mechanical works in Strasbourg before sailing to New York. Each locale added expertise in dynamos, regulation, and alternating current theory. Recognizing that ideas required both patent protection and dramatic demonstrations, Tesla navigated a landscape where scientific vision and industrial capital were inseparable.

Public Ministry

Tesla’s public career accelerated after his 1884 arrival in New York. Employed briefly at Edison Machine Works to improve dynamos, he soon clashed with Edison over the merits of alternating current. In 1886 he co-founded the Tesla Electric Light and Manufacturing Company, and with support from attorney Charles Peck and banker Alfred Brown he opened a South Fifth Avenue laboratory. There he perfected the polyphase induction motor—using rotating magnetic fields generated by out-of-phase currents—and filed foundational patents in 1887–1888. George Westinghouse acquired the licenses, inviting Tesla to Pittsburgh to adapt the system to industrial alternators. This alliance thrust Tesla into the “War of the Currents.” Backed by General Electric, Edison promoted direct current as safer, while Tesla and Westinghouse championed alternating current for its long-distance efficiency. Tesla’s 1891 lecture at the American Institute of Electrical Engineers introduced resonant coils and high-frequency phenomena, and he became a naturalized U.S. citizen the same year. His Houston Street laboratories showcased wireless lighting, high-voltage transformers, and mechanical oscillators, attracting journalists and investors. He endured setbacks—including a laboratory fire in 1895—but continued to patent innovations in motors, transformers, lighting, radio, and remote control. By the late 1890s Tesla was a celebrated lecturer in Europe and America. At the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Westinghouse illuminated the fair with Tesla’s polyphase system, while Tesla demonstrated wireless lamps and rotating magnetic fields. He contributed to the design of the Niagara Falls hydroelectric plant, which began operating in 1895 and validated alternating current distribution on a continental scale. These achievements cemented Tesla’s status as a chief architect of modern electrification.

Teachings And Message

Tesla paired his inventions with a sweeping vision of technological progress. He argued that science must alleviate human labor and extend light, power, and communication to underserved regions. In essays and lectures he described Earth as a vast conductor whose natural energy cycles—hydroelectric flows, atmospheric electricity—could be harnessed without burning fuel. He criticized the inefficiency of direct current and advocated international standardization of frequency and voltage. Humanistic themes permeated his message: Tesla believed that global electrical networks would foster peace by linking nations through instant communication. In Century Magazine (1900) he imagined a worldwide wireless system transmitting voice, images, and information, foreshadowing the internet. While warning against destructive military applications, he also explored defensive “teleforce” concepts. Tesla’s ascetic lifestyle, nightly work routines, and long walks exemplified his belief that disciplined habits nurture creativity. He famously claimed to visualize and test inventions entirely in his mind before building prototypes, a process that influenced later studies of creative cognition.

Activity In Galilee

Key locations defined Tesla’s creative output. In Budapest he experienced his 1882 epiphany about rotating magnetic fields while reciting Goethe’s Faust in a city park. In Paris he serviced dynamos for the Continental Edison Company, mastering practical engineering. In Strasbourg he built an induction motor prototype for the Société Alsacienne de Construction Mécanique, proving industrial feasibility. Across the Atlantic, his Manhattan laboratories hosted investors, reporters, and fellow scientists. The 1899 Colorado Springs facility, funded by Leonard Curtis, offered high-altitude isolation for experiments on atmospheric electricity and Earth resonance; Tesla recorded signals he interpreted as possible extraterrestrial transmissions. At Wardenclyffe on Long Island he constructed a 57-meter tower with buried iron pipes to conduct wireless energy worldwide. Although financial collapse halted the project, the site symbolizes his global ambition. Socially, Tesla mingled with industrialists like Westinghouse and financiers like Morgan, as well as cultural figures such as Mark Twain and Sarah Bernhardt, demonstrating his blend of scientific and artistic circles.

Journey To Jerusalem

Tesla’s major conflicts unfolded through economics and patents rather than politics. After Niagara Falls began operation, Westinghouse struggled financially; to preserve the alternating-current enterprise, Tesla reportedly tore up a lucrative royalty contract in 1897, sacrificing future wealth. Wardenclyffe exemplified another confrontation. Tesla secured initial backing from J. P. Morgan in 1901 to build a transatlantic wireless telegraphy tower, competing with Guglielmo Marconi. When Marconi achieved a transatlantic signal later that year, Morgan withheld further funding. Tesla, heavily indebted, mortgaged the property, but construction halted and the tower was dismantled in 1917 to satisfy creditors. Patent battles, especially with Marconi over radio priority, persisted for decades until the U.S. Supreme Court in 1943 acknowledged Tesla’s earlier filings—too late for him to benefit financially. Public skepticism of high-voltage demonstrations fueled additional strife. Edison’s anti-alternating-current campaigns featured sensational animal electrocutions, prompting Tesla to stage educational displays to prove safety. Media fascination with his idiosyncrasies—phobias of jewelry, solitary habits, nocturnal work—sometimes overshadowed his engineering accomplishments. Nevertheless he continued publishing essays on global power distribution, vertical-takeoff aircraft, and teleautomatics, maintaining confidence in humanity’s technological destiny.

Sources And Attestations

Tesla’s historiography draws upon a rich record of primary and secondary sources. His 1919 autobiographical series “My Inventions” in Electrical Experimenter details his methods and major breakthroughs. Patent filings between 1887 and 1928 document technical specifications for motors, transformers, radio apparatus, and remote-control boats. The archives of Westinghouse Electric, proceedings of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers, and the Colorado Springs laboratory notebooks provide additional evidence. Secondary scholarship by John J. O’Neill (Prodigal Genius, 1944), Marc J. Seifer (Wizard, 1996), and W. Bernard Carlson (Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age, 2013) contextualizes Tesla within industrial competition and media culture. IEEE Spectrum features and exhibitions at the Tesla Science Center at Wardenclyffe continue to update the public record. Contemporary testimonies by friends such as Mark Twain and the Johnsons portray his charisma and conversational range, while surviving photographs and lecture transcripts capture the theatrical dimension of his demonstrations.

Historical Interpretations

Modern historians strive to distinguish factual achievements from mythic embellishment. Popular accounts sometimes attribute to Tesla speculative inventions or conspiracies; scholarly studies instead assess the tangible impact of his patents, highlighting the successes of his polyphase systems and the speculative nature of his wireless-power schemes. Renewed interest in the 1990s and 2000s, fueled by digital culture and wireless technologies, recast him as a symbol of disruptive innovation. Analysts emphasize the tension between Tesla’s creative brilliance and his managerial struggles. His rivalry with Edison now appears as a clash of business models rather than a simple hero-villain narrative. Researchers credit collaborators such as Charles Scott and Benjamin Lamme for translating Tesla’s ideas into manufacturable equipment. Cultural historians note his influence on science fiction, maker communities, and the naming of the SI unit “tesla” for magnetic flux density. Debates continue regarding his later visions of global wireless power, yet consensus affirms his foundational role in electrifying the modern world.

Legacy

Tesla’s legacy spans engineering, culture, and humanitarian ideals. Polyphase power grids and induction motors remain the backbone of modern electricity networks. High-frequency research paved the way for radio, television, and wireless communication, while the Supreme Court’s 1943 decision on radio patents acknowledged his precedence. Museums in Belgrade, Smiljan, and Wardenclyffe preserve his laboratories and inspire STEM education. In popular culture he represents the idealistic inventor resisting financial constraints, appearing in novels, comics, and films. The automotive company Tesla, founded in 2003, underscores the resonance of his name with renewable energy and technological audacity. His writings on international cooperation, poverty reduction through electrification, and the peaceful use of science continue to influence debates on global energy access. Researchers still mine his notebooks for concepts relevant to twenty-first-century challenges.

Achievements and Legacy

Major Achievements

- Designed the polyphase induction motor and alternating-current distribution system

- Developed resonant coils and high-voltage transformers for wireless experiments

- Helped electrify the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair and the Niagara Falls hydroelectric plant

- Pioneered radio, remote control, and concepts of planetary communication

Historical Legacy

Nikola Tesla endures as the emblem of the visionary engineer whose inventions power global grids and inspire today’s energy transition.

Detailed Timeline

Major Events

Birth

Born in Smiljan to a Serbian Orthodox family

Arrival in the United States

Lands in New York and briefly joins Edison Machine Works

Polyphase patents

Licenses induction motor and system patents to Westinghouse

Chicago World’s Fair

Demonstrates alternating current and resonant coils at the exposition

Niagara Falls

Hydroelectric plant begins transmitting AC power using his system

Wardenclyffe Tower

Starts building a wireless transmission tower on Long Island

Death

Dies alone in his suite at the New Yorker Hotel

Geographic Timeline

Famous Quotes

"The present is theirs; the future, for which I really worked, is mine."

"If you want to find the secrets of the universe, think in terms of energy, frequency, and vibration."

"Science is but a perversion of itself unless it has as its ultimate goal the betterment of humanity."

External Links

Frequently Asked Questions

When was Nikola Tesla born and when did he die?

Nikola Tesla was born on 10 July 1856 in Smiljan, Austrian Empire, and died on 7 January 1943 in New York City.

What were his major contributions to electricity?

Tesla devised the polyphase induction motor, advanced high-voltage transformers, and outlined an alternating-current distribution system adopted worldwide.

Why did he clash with Thomas Edison?

Tesla championed alternating current for efficient long-distance transmission, whereas Edison promoted direct current; their rivalry defined the War of the Currents.

What happened at the Wardenclyffe Tower?

Tesla built Wardenclyffe on Long Island to pursue wireless telegraphy and global power transmission, but insufficient funding forced him to abandon the project, and the tower was dismantled in 1917.

Which historical sources document his life?

Primary evidence includes Tesla’s “My Inventions,” his U.S. patents, Westinghouse archives, and biographies by Marc Seifer and W. Bernard Carlson.

Sources and Bibliography

Primary Sources

- Nikola Tesla — My Inventions

- US Patent Office — Patents of Nikola Tesla

Secondary Sources

- Marc J. Seifer — Wizard: The Life and Times of Nikola Tesla ISBN: 9780806539968

- W. Bernard Carlson — Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age ISBN: 9780691165615

- IEEE Spectrum — Nikola Tesla Special Issue

External References

See Also

Specialized Sites

Batailles de France

Discover battles related to this figure

Dynasties Legacy

Coming soonExplore royal and noble lineages

Timeline France

Coming soonVisualize events on the chronological timeline